The Noigandres Poets and

Concrete Art

In 2006 we celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of two interconnected

events. The first was the trans-Atlantic baptism of a new kind of

poetry produced in Brazil by the “Noigandres” group of poets and in

Europe, as the Brazilians had recently found out, by Eugen Gomringer

and others, and which Gomringer in 1956 agreed to label “poesia

concreta / konkrete poesie / concrete poetry,” a label that

Augusto de Campos had first proposed for their own production a year

before. The second event was the opening of the “I Exposição

Nacional de Arte Concreta” in the Museu de Arte Moderna of

The first event established the

international presence of the Brazilians in a movement that was found

rather than founded as its members gradually discovered each other, and

that culminated (and ended) in the publication of several international

anthologies in the late sixties and in a number of exhibitions,

including a month-long “expose: concrete poetry” at Indiana University

in 1970.(1) The second event had no

international repercussions but turned out to be of considerable

significance for the Brazilian cultural scene of the day. It

established the label “Concrete Art,” and with it “Concrete Poetry,” in

the public mind. It was apparently the first exhibition in

While the Frente artists from

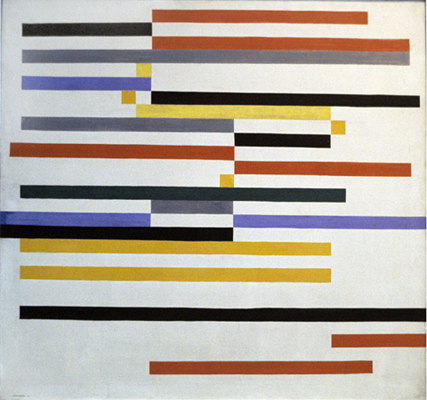

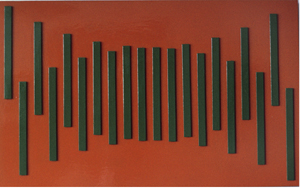

Fig. 1: Waldemar Cordeiro (1925-1973), Movimento

(Movement), 1951.

Tempera on canvas, 90.2 x 95 cm.

Contemporânea, Universidade de

São Paulo (USP).(8)

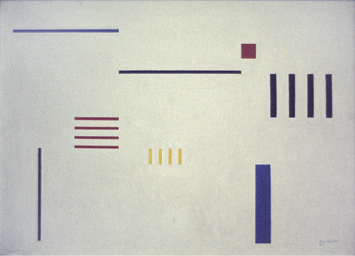

Luiz Sacilotto’s Concreção (1952;

fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Luiz Sacilotto (1924-2003), Concreção

(Concretion), 1952.

Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm.

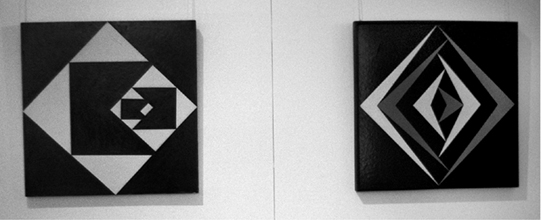

and Desenvolvimento de um quadrado and

Movimento contra movimento by Geraldo de Barros (both of 1952;

fig. 3).

Fig.3: Geraldo de Barros (1923-1998)

Left: Desenvolvimento de um quadrado

[Função diagonal] (Development of a Square [Diagonal Function]),

1952. Industrial lacquer on cardboard, 60 x 60 x 0.3 cm. Coll. Patricia

Phelps de Cisneros.(9)

Right: Movimento contra movimento (Movement

against Movement), 1952. Enamel on kelmite, 60 x 60 cm.

The reference to time or movement in the

titles that is characteristic of Ruptura work, as well as the use of

industrial media such as enamel or lacquer and of industrial board

(kelmite or eucatex) for the support, are also found in Objeto

rítmico No. 2 (1953; fig. 4) by Mauricio Nogueira Lima, who joined

Ruptura in 1953.

Fig. 4: Maurício Nogueira

“Pintura” on eucatex, 40 x 40 cm.

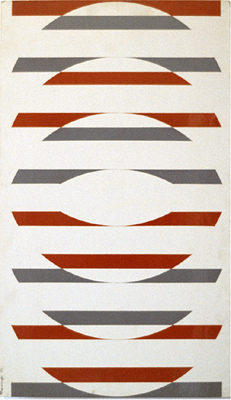

The apparent movement evoked by the design

is particularly intriguing in Círculos com movimento alternado

(1953; fig. 5) by Hermelindo Fiaminghi, who joined in 1955. The design

consists of an off-white vertical field traversed by coupled horizontal

bands in red and grey arranged in an alternating sequence which

reverses over the horizontal axis; its most effective feature is the

suggestion of a series of half-circles whose placement prevents the

upper halves from meeting the lower halves in a circle – which induces

the viewer to mentally moving them constantly closer or pushing them

apart in order to achieve the perfect circular form. The temporal

dimension is clearly perceived as a mental function induced by the

spatial design.(10)

Fig. 5: Hermelindo Fiaminghi

(1920-2004), Círculos com movimento alternado

(Circles with

Alternating Movement), 1956. Enamel on eucatex, 60 x 35 cm. (11)

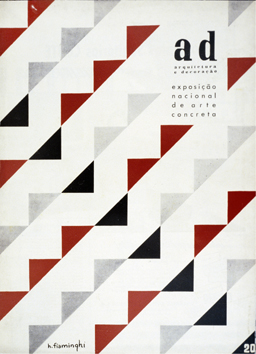

For the National Exhibition of 1956/57, an

issue of the magazine AD: Arquitetura e Decoração (No. 20, Dec.

1956) served as the catalogue and carried programmatic statements as

well as reproductions of artwork and poems. The cover (fig. 6) was

based on a painting by Fiaminghi that in 1977 was owned by the poet

Ronaldo Azeredo (fig. 7).(12)

Fig. 6: Cover, ad: arquitetura e

decoração (

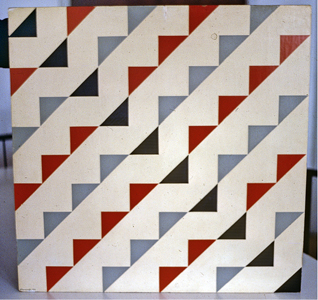

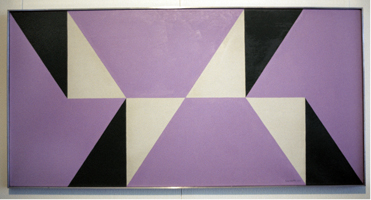

Fig. 7: Fiaminghi, Triângulos com

movimento em diagonal (Triangles with Diagonal

Movement), 1956. Enamel on eucatex, 60 x 60 cm.

Cordeiro opened his statement in the

catalogue by asserting: “Sensibility and the object encounter, at the

hands of the avant-garde, a new correlation.” He continued: “Art

represents the qualitative moments of sensibility raised to thought, a

“thought in images”. [ . . .] The universality of art is the

universality of the object. [ . . .] Art is different from pure thought

because it is material, and from ordinary things because it is thought.

[. . .] Art is not expression but product. [. . .] Spatial

two-dimensional painting reached its peak with Malevich and Mondrian.

Now there appears a new dimension: time. Time as

movement. Representation transcends the plane, but it is not

perspective, it is movement. (“O objeto”)

Besides later work by the Ruptura artists

already sampled, now less tentative and more sophisticated, the

“National Exhibition” included work by a founding member, Lothar

Charoux (fig. 8),

Fig. 8: Lothar Charoux (1912-1987),

Desenho (Design), 1956. Ink on paper,

49.3 x 49.2 cm.

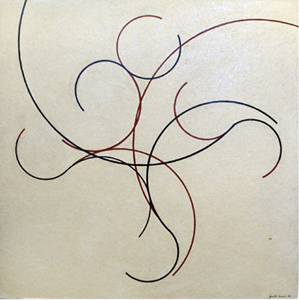

by Judith Lauand, who had joined the group

later (fig. 9),

Fig. 9: Judith Lauand (b. 1922), Variação

em curvas (Variation in

Curves), 1956. Enamel on eucatex, 60 x 60 cm.

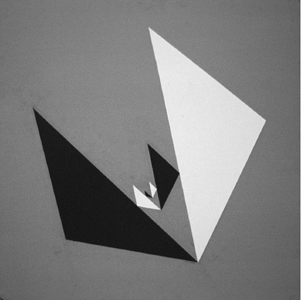

and by Alexandre Wollner, a close associate

but never a Ruptura member (fig. 10).

Fig. 10: Alexandre Wollner (b. 1928), Composição

em triângulos (Composition in Triangles),

1953. Enamel on duratex, 61 x 61 cm.

[Remade in 1977, after original in coll. Max Bill.]

All three are based on the square, the

preferred shape for much of the work by the Ruptura artists at the time

(cf. figs. 3, 4, 7, 12, 14, 26); all three confirm the tendency of

these Concrete artists’ designs to use “variation” and “development” of

lines and shapes by systematically altering their size and thus achieve

implications of a temporal dimension and the illusion of moving into

the depth of the field.

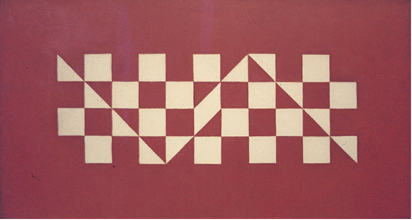

Alfredo Volpi, thirty years older than most

of the others and now counted among the very great in Brazilian art,

was for a number of years drawn onto the Concrete path. In his Xadres

branco e vermelho (fig. 11) he introduced into a static, flat,

decorative red-and white checkerboard pattern a dynamic ambiguity by

splitting diagonally descending squares diagonally into halves of

opposing colors, which inverts the pattern below the diagonal and

altogether confuses one’s optical orientation – which is only one of

the consequences of this simple intervention, more difficult to

verbalize than to grasp visually.

Fig. 11: Alfredo Volpi (1896-1988), Xadres

branco e vermelho (White and Red Checkerboard),

1956. Tempera[?]

on canvas, 53 x 100 cm.

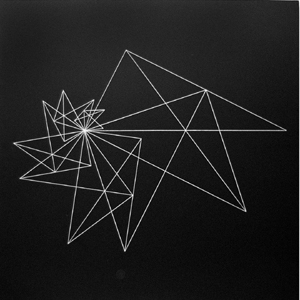

A black-and white reproduction of Volpi’s

painting was reproduced in the ad catalogue, and so was

Mauricio Nogueira Lima’s Triângulo espiral (fig. 12), a black

square in which a set of interlocking triangles follows a systematic

pattern of development that imposes a rotation either inward to the

left, with regular diminutions, or outward to the right, with the

triangles increasing, so that the spiral movement may suggest either an

implosion or an explosion.

Fig. 12: Mauricio Nogueira

Paint on eucatex, 60 x 60cm.

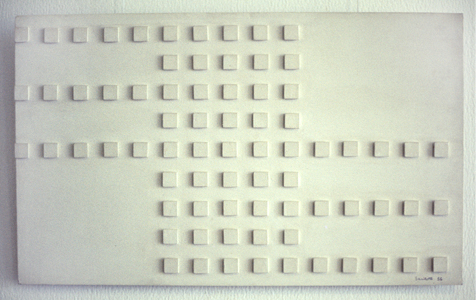

A striking example of the use of industrial

material with a suggestion of manufacturing processes was Sacilotto’s Concreção

5624 (fig. 13);(13) its uneven surface

resulting from pasting on identical small aluminum squares in a

rigorous pattern introduced into the monochrome work a play of light

and shadows that changed with the position of the observer.

Fig. 13: Luiz Sacilotto, Concreção

5624, 1956. Oil on aluminum,

36.5 x 60 x 0.4 cm.

Coll. Renata Feffer.

In keeping with the slogan “the work of art

does not contain an idea, it is itself an idea,”(14)

Cordeiro entitled many of his paintings of that time “Visible Idea”;

figure 14 shows one version of a series developing this particular

idea, or theme.(15)

Fig. 14: Paint and plaster on plywood

The impersonality of their work of the

1950s made it at times difficult to recognize authorship, but – as

these examples will have demonstrated – differences existed and would

eventually become more pronounced; however, for a number of years the

members of the Ruptura group adhered quite faithfully to their program

The materials of their paintings (straight or curved lines, geometric

shapes, a few carefully balanced colors used for structural effect)

were reduced to a minimum; all signs of individual production, such as

brushstrokes, were eliminated. The only self-expression they permitted

their work to show was the expression of their particular way of visual

thinking and of the ways in which they conceived and executed “visual

ideas.” Every work followed a clear plan which could be formulated as

verbal instructions to be executed by someone else; and a realization

of the rules governing each “visible idea” was a necessary part of the

viewer’s experience and understanding. In the case of Cordeiro’s

painting shown in figure 14 we see two sets of angled straight lines,

one in red, the other in black, placed so asymmetrically that they

hardly invade the left half of the white square, but with the implied

movement producing a sense of visual balance. The black lines function

as it were in counterpoint to the mechanically regular progression of

the identical angular lines in red, except for the reverse angle in the

final line that braces the movement; yet the effect on the perception

and visual imagination is not mechanical at all. Spatial

relationships become ambivalent, and a major characteristic of this

minimalist work is its rhythmic dynamism.

The work of these artists, much of which

was undertaken as a kind of “pesquisa” (research), an exploration of

the possibilities of the medium, created indeed a sense of movement,

differently induced in each case and mentally executed by the viewer.

“The painters, designers and sculptors from São Paulo not only believe

in their theories but also follow them, at their own risk”, wrote the

influential critic Mário Pedrosa in response to the exhibition of

1956/57, contrasting them with the artists from Rio, whom he considered

“almost romantics” by comparison. (16) Indeed,

the poet and critic Ferreira Gullar, who was to become their major

spokesman, confirmed:

The Grupo Frente did not have at least two

of the characteristics that are common to avant-garde

movements: the defense of a single stylistic orientation and a

theoretical underpinning. [. . .] Nevertheless, it played a role in the

renovation of Brazilian art [. . .] (“O Grupo Frente” 143)

A number of the artists from

No matter what the merits of this

criticism, both their work and their theoretical statements

confirm the affinities between the Noigandres poets and the Ruptura

artists. Cordeiro met Décio, Haroldo and Augusto in November 1952,

when they had just published the first issue of Noigandres with

their recent poems and the Ruptura artists were about to open their

exhibition. I do not know much about the intensity of the contacts

in the years before the National Exhibition, but some of the Ruptura

members have been called “interlocutores constantes” with the

poets. In 1953 Décio and Cordeiro traveled together to

All of these poems are inscribed in

invisible squares. All contain at least two colors, with the sixth, “dias dias dias,” displaying all of the primary

and secondary colors as well as lower-case and capital letters.

Inspired by the composer Anton von Webern’s theory and practice of Klangfarbenmelodie,(18) published.(19) The most frequently discussed poem is

“lygia,” reproduced and analyzed (again) in Marjorie Perloff’s essay; I

have shown elsewhere, following Augusto’s own lead, that the poem is in

fact (among other things) a transposition of the opening measures of

Webern’s Quartet for Violin, Clarinet, Tenor saxophone and Piano, op.

22 (Clüver, “Klangfarbenmelodie”).

In the newspaper articles Augusto and

Haroldo began to publish in 1955 there was apparently no reference to

Brazilian Concrete art. When the “plano-piloto da poesia concreta”

(Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry), the condensed summary of the

theoretical statements composed by the two and Décio over the past four

years and published in 1958 in Noigandres 4, defines Concrete

poetry as “tension of word-things in space-time” and lists parallels in

music and the visual arts, it refers to “mondrian and the boogie-woogie

series; max bill; albers and the ambivalence of perception; concrete

art in general.” It is difficult and also rather pointless to speculate

on the effect the personal contacts may have had on the thoughts and

the work of poets or painters during the years leading up to the

National Exhibition.

But the affinities are obvious. In

hindsight, considering them from the “orthodox” (or “heroic”) phase

that their work had reached with the poems published in Noigandres

4, Augusto’s Poetamenos poems still show a number of

characteristics that were later eliminated (which, for some readers,

may make them more interesting and appealing). There is still a

lyrical “I” present – in fact, in terms of referential content they are

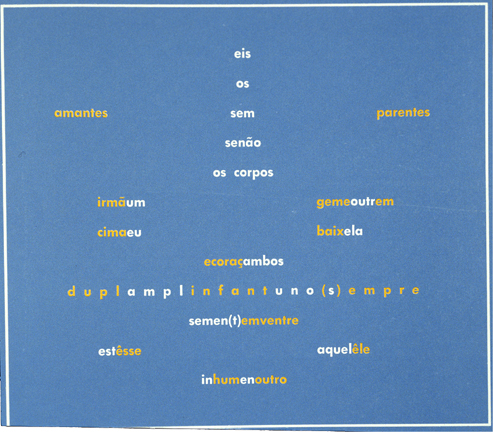

a kind of Erlebnislyrik. The fifth poem, “eis os amantes,”

using a more reduced verbal material and approaching the isomorphism so

strongly emphasized in the “Pilot Plan”, indicates most clearly the

path future developments will follow.

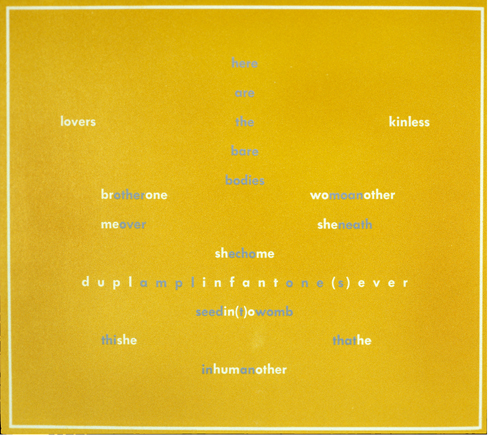

Fig. 15a: Augusto de Campos (b. 1931), “eis

os amantes” (1953/55),

from Solt, ed., Concrete Poetry, recto

of inside cover page.

Fig. 15b: Augusto de Campos, “here are the

lovers,” trans. A. de Campos, Marcus Guimarães

and Mary Ellen Solt , from Solt, ed., Concrete

Poetry, verso of inside cover page.

Originally published in the complementary

colors blue and orange,(20) it was placed in

white and orange within a blue square for its publication in Mary Ellen

Solt’s Concrete poetry anthology (fig. 15a), with the

English translation appearing in blue and white in an orange square

(fig. 15b).(21) The semantic representation of

the sexual union of two lovers, culminating in the long portmanteau

word in the center and the final verbal fusion of one in the other

continuing the “infant” motif, is visually shown by the placement,

approximation, intertwining and crossing of the two colors. Noigandres

3 was published on the occasion of the 1956 exhibit, with poems by

Décio Pignatari, Haroldo and Augusto de Campos, and Ronaldon Azeredo.

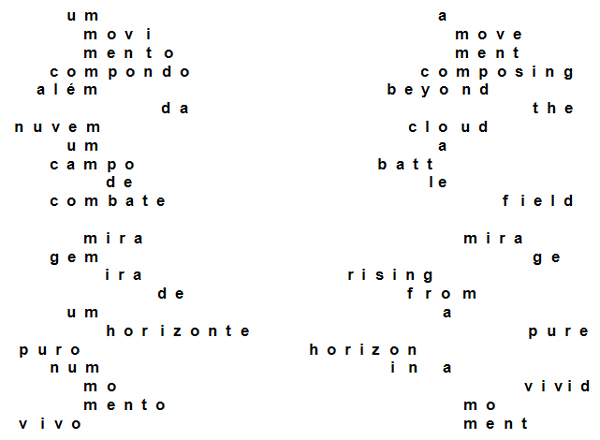

Pignatari’s “um movimento” was also included in the ad

catalogue as a typewritten text. I reproduce it below with an attempt

at a translation that makes compromises in order to somehow preserve

its most salient features. It is (still) a syntactically coherent

statement complete with a verb (a participle, “compondo”) and separated

by an empty line into two stanzas. But the most striking feature

is the column of m’s in the center (making it into a kind of Mittelachsengedicht),

which emphasizes its spatial properties and invites the exploration of

other vertical relations and internal visual structures. The entire

shape suggests an iconic relation to its semantic content, a

(metaphoric?) landscape or cloudscape, which moves from “a movement” to

“a moment”, with “horizonte” representing the most prominent horizontal

feature. There is still an implied observer and therefore the expressed

presence of a consciousness.

Fig. 16: Décio Pignatari (b. 1927), “um movimento,” from Noigandres 3, 1956; English version: Claus Clüver.

Composed in the same year but not included

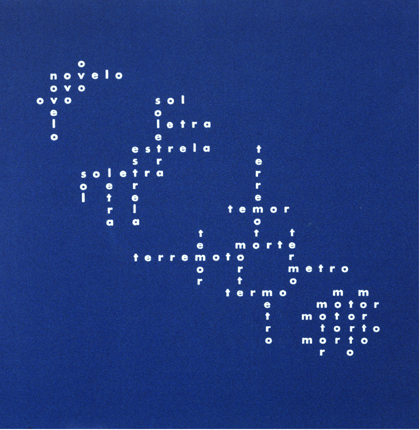

in Noigandres 3, Augusto’s “terremoto” (earthquake) (22) (fig. 17) has a purely spatial syntax,

although conceptually, in its lexical references, it develops a

temporal theme of cosmic proportions. Its “stanzas” descend diagonally

from top to bottom, although each of these interlocking open squares is

internally developed both horizontally and vertically (Augusto has

referred to it as a Concrete crossword-puzzle). There is a sense

of expansion and contraction; the last stanza is a dense ball dominated

by o’s and t’s (which in the Futura

typeface look like crosses). This ball refers us both visually and

conceptually back to the o’s of the egg (“ovo”) and the ball of yarn

(“novelo”) of the opening and thus suggests a circularity that is found

in a number of poems of the later phase, formally expressing the

space-time dimension emphasized in the “Pilot Plan,” which is there

likened to the same phenomenon represented “in concrete art in general.”

Fig. 17: Augusto de Campos,

“terremoto” (1956), version published

in Solt, ed., Concrete Poetry, np.

The poem was originally published in black

on a white page; the version shown here, which shows the letters in

white inscribed in a dark blue square, visually evokes a stellar

constellation, in keeping with part of the dominant imagery. This

iconic emphasis may subdue other implications and associations evoked

by the text; but Augusto has agreed that a white-on-black reproduction

may be appropriate (just as two of Haroldo’s contributions to Noigandres

3 offered a white text against a black ground).

In “arte concreta: objeto e objetivo,” the

programmatic opening statement of the catalogue, Décio Pignatari

emphasized that:

Verse having been abolished, Concrete poetry confronts many problems of space and time (movement) that both the visual arts and architecture have in common, not to speak of the most advanced (electronic) music. Moreover, the ideogram, for example, can perfectly well function on a wall, internal or external. (ad, no. 20, np.)

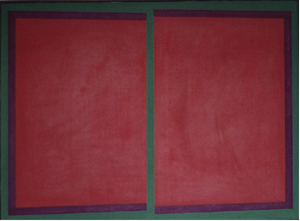

Obviously, the experience of showing their

work side by side with paintings and sculptures determined the poets’

decision to publish Noigandres 4 (1958) as a portfolio edition

with twelve poster poems, ready to be displayed. It had a cover by

Fiaminghi (fig. 18). With these poems, the production of the four had reached the most

characteristic form of the Concrete “ideogram,” as they called

Fig. 18: Cover of Noigandres 4,

1958; design: Hermelindo Fiaminghi.

their

texts as disciples of Ezra Pound. To a considerable degree, its

characteristics can be described by the same terms that I used to

indicate basic aspects of the paintings of the Ruptura members – which

is obviously the reason why they decided to exhibit their work

together, under the “Concrete” label. Reducing their verbal

material to a minimum, the poets were engaged in exploring its inherent

possibilities by structurally exhibiting the interplay of its visual,

aural, and semantic properties. Because of the importance they

continued to attach to semantics, they never worked with less than a

word, although the word could be subjected to processes of

fragmentation and permutation. The structure achieved by arranging the

verbal elements in the space of the page according to a text-specific

strategy can be considered as analogous to Cordeiro’s “visible idea.”

No structural procedure is ever repeated; while construction is

rule-bound, it is always tied to the semantics of the material in order

to achieve what the poets would call an “isomorphism,” an iconic

relationship between the verbal sign and its

signified (see Clüver, “Iconicidade”). Arranged according to a spatial

syntax, these seemingly simple texts would frequently allow for

multidirectional readings and return the reader to the

beginning. With the abolition of traditional linear progression

the poems would establish spatio-temporal relations that linked them to

the Ruptura paintings also in this respect. Eliminating any notion of a

“persona” or self-expressive lyrical “I”, the Concrete ideogram was

designed to be an “objeto útil”, a useful textual object to be

contemplated and explored, “open” (23) enough

to allow readers to “use” it according to their own ingenuity, but with

the expectation that they would respect the rules of the game inherent

in the structure. In an interview about the National Exhibition of

1956, Augusto has quite recently explained the polemical use of such

phrases as “useful object”:

It is obvious that certain characteristics of the new poetry were

carried by us to the limit, in the case of

terms and themes such as that of the “mathematics of composition” and

of “poem: useful object.” But I think that this radical attitude was

necessary in view of the self-complacency and sentimentalism dominant

in our midst. I saw in the “sensible rationalism” on which we

insisted the fundamental objective of poetry itself: to achieve a

production where not a word, not a letter could be changed,

where no part of the text could be moved without having the

poem collapse – which is, after all, the goal of every poet. (24)

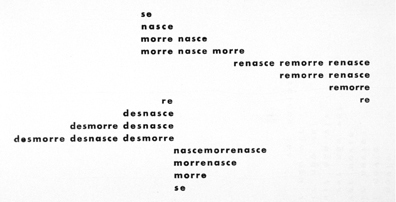

I have used Haroldo de Campos’s poem

“nascemorre” (fig. 19) on an earlier occasion (25)

to show how a change of the minutest detail can destroy a major

structural effect: the first triangle formed by a regular (if you like

mathematical) development of the minimal verbal material (“se nasce morre”, if he/she/it is born

he/she/it dies) re-constructs itself by seemingly turning over an

invisible horizontal

Fig. 19: Haroldo de Campos

(1929–2003), “nascemorre,” Noigandres 4, 1958.

and a structurally designated vertical axis formed

by carefully aligned “re”s; a shift of the second triangle by one slot

to the left (as it has happened in the fine anthology organized by Mary

Ellen Solt) not only removes that axis but violates the structural

feature of vertically aligning all e’s of the text except for those of

the initial and final “se.” Altogether the poem exhausts all the

possibilities inherent in its semantic properties as well as of the

visual arrangement of its triangles. The final syllable (an echo

of “nasce”) returns us to the beginning in an endless progression of

dying and becoming.

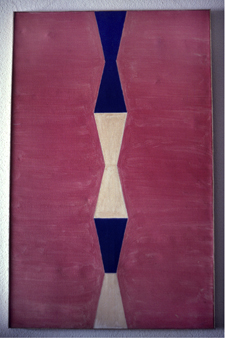

In visual terms, the poem’s structure is

quite similar to Sacilotto’s Concreção 6048 of 1960, which also exhausts all the possibilities of

combining the black and white triangles and of placing the pairs that

are inherent in the design. Such similarities could be found in

structural comparisons of several poems with works by Ruptura artists. But the triangles and the placement of the pairs in Sacilotto’s painting

Fig. 20: Luiz Sacilotto, Concreção

6048, 1960. Oil on canvas,

60 x 120 cm.

obviously have a different motivation and function

than those in Haroldo’s poem, where each triangle manifestly performs

the act of “becoming” signaled by the verbal semantics and the “death”

of the first triangle leads to its “rebirth” in the second and the

inversion of the second also inverts the meaning of the verbs:

“desnasce” equals “morre.” On the other hand, as I hope to have shown,

the similarities between the work of both

groups in their orthodox Concrete phase reach significantly deeper.

The two latest members to join the

Noigandres group tended to work with the least amount of verbal

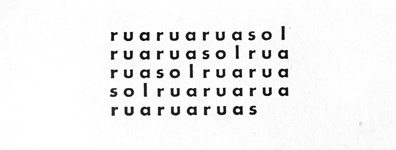

material. In “ruasol” (fig. 21) by Ronaldo Azeredo, the word “sol”

(sun) seems to move through the visual field formed by repetitions of

“rua” (street), only to return as a trace (an s) in the last line, where the s simultaneously

turns “rua” into a plural – only “ruas” is left when “sol” is gone. But our

Fig. 21: Ronaldo Azeredo (1937–2006),

“ruasol,”, Noigandres 4, 1958.

reading of this text will not stop with recognizing its

representational and iconic qualities; of greater interest is the

exploration of the verbal material and its signifying properties on

which the poem’s isomorphism is based – and of the kind of isomorphism

embodied in this text. (26)

The most rewarding way to read the poems

under consideration here is to approach them as metapoems – which in

this case includes the observation that “ruasol” is intranslatable,

because only Portuguese uses three letters to form each of the two

nouns signifying “street” and “sun.” An effort to understand how the

text functions is very similar to the effort of understanding a

Concrete painting or sculpture.

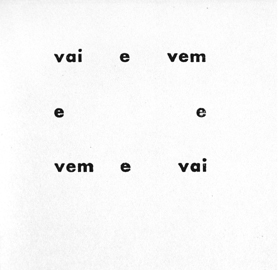

A poem that seems to “say” even less is

José Lino Grünewald’s “vai e vem” of 1959 (fig. 22). Here are some

notes by the filmmaker Stefan Ferreira Clüver, who in 1980 based an

18-minute film on this poem:

Two simple, formal transformations of a commonplace generate some very

complex possibilities for meaning

making. First, by violating the syntactic closure of the phrase

“vai e vem” with a repetition of the “e” at its end, a regular verbal

pattern is created that can go on indefinitely: ABA becomes

ABAB. Second, by giving this syntactic alteration a graphic

statement that connects beginning and end, the way in which the now

endlessly repeating phrase signifies is radically altered: it becomes

an ideogram. This ideogram, however, is quite different from those

in current writing systems that have become as conventional as

letter-based ones. The poem generates its own rules for making

meaning because, as an ideogram, it can only be understood as a graphic

violation of the linear, cumulative signifying conventions of language.

The poem’s arrangement on the page creates

a tension between a syntactic dynamism and graphic stasis. The

verbs “vai” and “vem,” normally words of action, become the visual

resting points of the graphic, while the conjunction “e” is the visual

motor. “Vai” and “vem” become thing words,

“e” becomes the movement word. (27)

Fig. 22: José Lino Grünewald

(1931–2000), “vai e vem” (1959), Anthologia Noigandres 5, p.

181.

In 1962 the five “Noigandres” poets (now

also including Grünewald) collected their published poems and quite a

few unpublished ones in antologia noigandres 5: do verso à poesia

concreta, with a cover (fig. 23) based on a painting by Volpi owned

by Pignatari (fig. 24). The anthology concluded the “heroic” phase of orthodox Concrete poetry produced by the Noigandres poets, at about the same

Fig.

23: Cover, antologia noigandres 5, 1962.

Fig.

24: Alfredo Volpi, 1960, Coll. D. Pignatari.

time that the Ruptura artists began to strike out in individually more

distinct and separate ways, as did the poets. The contacts among

artists and poets continued. When I began my research in

Fig.

25: Mauricio Nogueira

Fig. 26: Hermelindo Fiaminghi, 1956., Coll. D. Pignatari.

In Ronaldo Azeredo’s home I found these two

small paintings by Volpi and one by Sacilotto,

Fig.

27: Alfredo Volpi, two paintings, Coll. Ronaldo Azeredo...

Fig.

28: Luiz Sacilotto, 1958, Coll. Ronaldo Azeredo.

as well as this work by Nogueira Lima

(besides the Fiaminghi painting shown in fig. 7):

Fig. 29: Mauricio Nogueira

Lima, 1960. Coll. Ronaldo

Azeredo.

Augusto owned a painting by Sacilotto that

I did not photograph; Haroldo’s living-room wall was full of paintings,

but there my son filmed while I was taping my interviews, and so I have

no slides.

I have limited my remarks to the decade

surrounding the National Exhibition and to the relations of the

Noigandres poets to Concrete art produced in

On the other hand, the sculptors from Rio

participating in the National Exhibition, Franz Weissmann, a Frente

member, and Amilcar de Castro, long associated with the group, continued throughout their career to

develop a line of work that retained close affinities to the Concrete

aesthetic; some of their later work is found in public places also in

Fig. 30: Franz Weissmann (1911–2005), Coluna

(Column), 1958. Painted iron, 280 x 110 x 75 cm.

São Paulo: Museu de Arte

Contemporânea, USP. Photo:

Claus Clüver, 1977.

squares

rather than on their sides, the new column was lighter and less

austere. The basic idea on which the column is built is also found

in another sculpture displayed in the 1977 exhibit, Três pontos (fig.

31). The artist told me in an interview in 1981 that he had hoped to

see it placed, in a larger scale, in the center of Brasília, to

symbolize the interplay and intricate balance among the three branches

of government.

Fig. 31: Franz Weissmann, Três

pontos (Three Points), 1958. Painted iron,

120 x 160 x 160 cm. Photo: Claus Clüver,

1977.

The sculpture that stood at the entrance of

the exhibit in Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Modern Art, Weissmann’s Círculo

inscrito num quadrado (fig. 32), shows one of the simplest forms

of the idea of creating interlocking squares out of flat sheets of

metal and “inscribing” in them circles by cutting them out; here, the

squares rest on their sides.

Fig. 32: Installation shot, “Projeto

Construtivo Brasileiro na Arte (1950–1962)”,

Museu de Arte Moderna, 1977, with Franz

Weissmann, Círculo inscrito num quadrado

(Circle Inscribed in a Square), 1958. Painted iron, 100 x 100 x 100 cm. Photo by Claus Clüver.

Amilcar de Castro’s work is characterized

by a seemingly intuitive approach and the great simplicity by which he

creates spatial configurations by cutting and bending “flat” circular

(fig. 33) or square (fig. 34) steel plates. I first saw a display of

some of his sculptures in 1976 in

Fig. 33: Amilcar de Castro

(1920–2002), steel sculpture displayed in front of the

Palácio das Artes in

Fig. 34: Amilcar de Castro, steel

sculptures displayed in the courtyard of the

Palácio das Artes in

.

The work of both sculptors clearly shares

the Concrete aesthetic exemplified by the paintings, sculptures, and

poems shown in the National Exhibition of 1956/57. It was not even then

a unified aesthetic, and the rupture

between Cariocas and Paulistas that was to occur soon after and to turn

into a split between Concrete and Neoconcrete art (and poetry) brought

into greater relief what an attentive observer like Mário Pedrosa noted

right away. But much of the public reaction involved an attempt to come

to terms with the radical break with tradition perceived in all of the

work, and most specifically in the poetry, because constructivist

visual art produced in

This essay has focused on the

interrelations between the work of the Ruptura artists and of the

Noigandres poets, and on the interactions among its members. As a

consequence of the juxtaposition and of the exploration of analogies

and similarities, access to these works may have become easier; even

nowadays, “reading” these texts – paintings, sculptures, and poems – is

still a considerable challenge for many.

And the way we read them has changed in the

course of fifty years. We are looking back at them with a knowledge of what has been produced since –both

by the artists and poets themselves and by the culture that shaped them

and that they have shaped in turn. The critical discourse has changed:

not only have post-modern notions about the nature and function of art

affected the way we approach these visual and verbal texts, but we have

witnessed a lively debate about the construction of avant-gardes and

neo-avant-gardes based on a well-mapped landscape of the earlier part

of the century that may be at odds with the information that was

available to the young Brazilians at mid-century.

What is also beginning to change, to some

extent under the impact of the new media and of the intermedial

genres of textmaking they are generating, is the habit of looking at

such events as the National Exhibition of 1956/57 through the limiting

lenses of the traditional disciplines. The

developing field of Studies of Intermediality will provide a more

appropriate perspective and better tools to look at such intermedial

phenomenon as Concrete poetry. Even now, the semicentennial

celebrations have by and large looked at it as a literary event. The

insistence of the Noigandres poets on listing in the “Pilot Plan”

not only Mallarmé, Pound, Joyce, Cummings, and Apollinaire as well

as the Brazilian poets Oswald de Andrade and João Cabral de Melo Neto

as “precursors”, but pointing to aspects of the work of Eisenstein and

Webern as well as of Mondrian, Max Bill, Josef Albers and “Concrete art

in general” as providing signposts for the new poetry (and art) to be

“invented” has had little impact on the critical discussion. Nor have

the references to the other arts in the poems themselves received much

attention. (29) For

the poets, their participation in the exhibition was a defining moment.

They saw their work as constituting part of the new avant-garde that

was to shape their country’s cultural production – and possibly turn it

from the post-colonial “anthropophagic” consumer of foreign models into

a supplier itself of “models for export.”(30)

To some degree, the poets have succeeded;

they occupy an often privileged position in relevant international

anthologies and exhbition catalogues, (31)

although many of their manifestos and theoretical statements collected

in their Teoria have for the most part remained untranslated.

The Ruptura artists have remained almost entirely unknown abroad, for

reasons that have little to do with their work and everything with the

international art scene. But their impact within the country, along

with that of the Neoconcretos, can be assessed by the number of

memorial exhibitions I listed earlier, besides a growing number

of studies devoted to Brazil’s “Constructivist Project” in general

(32) or monographs on individual artists.(33) The publications accompanying and

documenting the exhibitions (34) included

material about Concrete (and Neoconcrete) poetry; in the monographs the

connection between Concrete art and poetry is not a topic. Art critics

and historians have disregarded the intermedial and intersemiotic

dimensions of the Brazilian avant-garde of the fifties just as much as

their literary counterparts. This essay provides no more than a modest

orientation.

Appendix

Visual Artists

Notes (1). The major anthologies are

listed in the Bibliography of Clüver, “Concrete Poetry: Critical

Perspectives.” The month-long international exhibition at (5). See Augusto de Campos, Interview, 2006. The

exhibition “concreta ’56: a raiz da forma” was held in the Museu de

Arte Moderna of (6). See the “Appendix” for a list of participants. References AD: Arquitetura e

Decoração ( Aldana, Erin. “Waldemar

Cordeiro, Idéia visível [Visible Idea], 1956.” In

Pérez-Barreiro, ed. The

Geometry of Hope, 148–50. Amaral, Aracy, ed. Projeto

Construtivo Brasileiro na Arte (1950–1962).

Exhibition

catalogue. Rio de Janeiro: Museu de Arte Moderna; São

Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado, 1977. Amaral, Aracy, ed. Arte

Construtiva no Brasil: Coleção

Adolfo Leirner. Portuguese and English. São Paulo: DBA

Artes Gráficas, 1998. Arte Concreta Paulista. 5 vols. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2002. See: (1) João Bandeira; (2) Rejane Cintrão; (3) Lenora de Barros and Joo Bandeira; (4)

Helouise Costa; (5) Regina Teixeira de Barros. João Bandeira, org. Arte Concreta Paulista:

Documentos. Exhibition catalogue, Centro Universitário Maria

Antônia da Universidade de São Paulo. So Paulo: Cosac

& Naify; Centro Universitário Maria Antonia da USP, 2002. Barros, Lenora de, and João Bandeira, curators. Grupo Noigandres. Exhibition

catalogue, Centro Universitário Maria Antônia da Universidade de São

Paulo. Barros, Regina Teixeira de, ed. Antonio Maluf.Texts:

Regina Teixeira de Barros and Taisa Helena P. Linhares. Exhibition

catalogue, Centro Universitário Maria Antônia da Universidade de São

Paulo. Belluzo, Ana Maria. Waldemar Cordeiro: Uma aventura da

razão. São Paulo: Museu de Arte Contemporâneo de São Paulo, 1986.[P-B 334] Blistne, Bernard, and Véronique Legrand, orgs. Poésure et Peintrie: «d'un art,

l'autre». Exhibition catalogue, Centre de la

Vieille Charité, Marseille, 12 February – 23 May 1993. Marseille:

Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Musées de Marseille, 1993 [1998?]. Brito, Ronaldo. Amilcar

de Castro. Fotos Rômulo Fialdini et al. Cabral, Isabella, and M. A. Amaral

Rezende. Hermelindo Fiaminghi.

Artistas Brasileiros, 11. Campos, Augusto de.

http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/poemas.htm Campos, Augusto de, Décio Pignatari and Haroldo de Campos,

“plano-piloto para poesia concreta.” Noigandres 4 (1958). Rpt. in English:

“plano-piloto para poesia concreta / pilot plan for concrete poetry.” Portuguese and English, tr. by the authors. In

Solt, ed. Concrete Poetry: A World View.70–72. “pilot plan for concrete poetry.” Tr. Jon M. Tolman. In Richard Kostelanetz, ed. The Avant-Garde

Tradition in Literature. Campos, Haroldo de. “A Obra de Arte Aberta” (orig. 1955). Rpt. in Cintro, Rejane, curator. Grupo

Ruptura: Revisitando a Exposiço Inaugural. Texts by Rejane Cintrão and Ana Paula Nascimento. Exhibition catalogue, Centro Universitário Maria Antônia da

Universidade de São Paulo. Clüver, Claus. “Augusto de Campos’s ‘terremoto’: Cosmogony as

Ideogram.” Contemporary Poetry 3.1 (1978): 38-55. Clüver, Claus. “Brazilian Concrete: Painting, Poetry, Time,

and Space.” In Proceedings of the IXth

Congress of the International Comparative Literature Association.

Vol. 3: Literature and the Other Arts. Ed.

Zoran Konstantinović, Ulrich Weisstein, and Steven Paul Scher. Clüver, Claus. “Concrete Poetry: Critical Perspectives from

the 90s.” In K. David Jackson, Eric Vos, and Johanna Drucker, eds..Experimental – Visual – Concrete: Avant-Garde Poetry

Since the 1960s. AvantGarde

Critical Studies, 10. Clüver, Claus. “Iconicidade e

isomorfismo em poemas concretos brasileiros.” Trans. André Melo Mendes. Dossiã: 50 anos da poesia Concreta.

Ed. Myriam Corra de Araújo Ávila et al. O eixo e a roda (FALE, Universidade

Federal de Minas Gerais), no. 13 (July–Dec. 2006): 19–38. Clüver, Claus. “Klangfarbenmelodie in Polychromatic

Poems: A. von Webern and A. de Campos.” Comparative Literature

Studies 18 (1981): 386-98. Clüver, Claus. “On Intersemiotic

Transposition.” In Art and Literature I,

ed. Wendy Steiner. Topical issue. Poetics

Today 10.1 (1989): 55–90. Clüver, Claus.“The ‘Ruptura’

Proclaimed by Clüver, Stefan Ferreira. “Viewing Notes

by the Filmmaker” on vai e vem, a film from the poem of José

Lino Grünewald, 1980/1998. 1998, unpublished. Cordeiro, Waldemar. “O objeto.” AD: Arquitetura e

Decoração ( Gullar, Ferreira. “O Grupo

Frente e a Reação Neoconcreta / Frente Group and the

Neo-Concrete Reaction.” In Amaral, ed., Arte

Construtiva no Brasil, 143–81. Gullar, Ferreira. “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” Jornal do Brasil ( Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo. Catálogo Geral das Obras. Orientação:

Walter Zanini. São Paulo: MAC/USP, 1973. O Museu de Arte

Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo.São

Paulo: Banco Safra, 1990. Noigandres (São Paulo,

authors’publication):

No. 1, 1952; No. 2, 1955; No. 3, 1956; No.

4, 1958 (folder with poster poems).

Antologia Noigandres 5: do verso ã poesia concreta. Pape, Lygia, curator. Projeto Construtivo Brasileiro na

Arte (1950–1962). Exhibition catalogue. Museu de Arte Moderna

do Rio de Janeiro / Pinacoteca do Estado de São

Paulo, 1977. 20 pp. Pedrosa, Mário. “Paulistas e Cariocas”

(Feb.1957). Rpt. in Amaral, ed. Projeto Construtivo

Brasileiro na Arte, 136–38. Pérez-Barreiro, Gabriel. “Geraldo de Barros, Função

diagonal [Diagonal Function], 1952.” In

Pérez-Barreiro, ed. The

Geometry of Hope, 128–30. Pérez-Barreiro, Gabriel, ed. The

Geometry of Hope: Latin American Abstract Art from the Patricia Phelps

de Cisneros Collection. Exhibition catalogue,

Blanton Museum of Art, U Texas, Pignatari, Décio. “Arte concreta: objeto e objetivo.” AD: Arquitetura e Decoração ( Solt, Mary Ellen, ed. A World

Look at Concrete Poetry. Topical double issue.

Artes Hispanicas / Hispanic Arts 1.3-4

(1968). Rpt. as M.E. Solt, ed. Concrete Poetry: A World View.

Salzstein, Sônia. Franz

Weissmann. Espaços da arte brasileira. Silva, Fernando Pedro da, and Marília

Andrés Ribeiro, coord. Franz

Weissmann: Depoimento. Organização e

entrevista do livro: Marília Andrés Ribeiro Belo Horizonte: C/ arte,

2002. Stolarski, André. Alexandre Wollner e a formação do design moderno no Brasil .

List of Works Shown Fig. 1: Waldemar

Cordeiro (1925-1973), Movimento (Movement), 1951. Tempera on

canvas, 90.2 x 95 cm. São Paulo: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Universidade

de São

Paulo (USP). Fig. 2: Luiz

Sacilotto (1924-2003), Concreção (Concretion),

1952. Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm. São Paulo: Coll. Ricard Akagawa. Fig. 3: Geraldo de Barros

(1923-1998) Left: Desenvolvimento de um quadrado [Funço diagonal]

(Development of a Square [Diagonal Function]), 1952. Industrial lacquer

on cardboard, 60 x 60 x 0.3 cm. Coll. Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. Right: Movimento contra movimento

(Movement against Movement), 1952. Enamel on kelmite, 60 x 60

cm. Switzerland: Coll. Fabiana de Barros. Fig. 4: Maurício

Nogueira Lima (1930-1999), Objeto rítmico No. 2 (Rhythmic

Object No. 2), 1953. “Pintura” on eucatex, 40 x 40 cm, São Paulo: Coll. Luiz

Sacilotto. Fig. 5: Hermelindo

Fiaminghi (1920-2004), Círculos com movimento alternado

(Circles with Alternating Movement), 1953. Enamel on eucatex, 60 x 35

cm. Fig. 6: Cover, ad: arquitetura e

decoração, No. 20, December 1956. Fig. 7: Fiaminghi,

Triângulos com movimento em diagonal (Triangles with Diagonal

Movement), 1956. Enamel on eucatex, 60 x 60 cm. São Paulo: Coll. Ronaldo Azeredo. Fig. 8: Lothar

Charoux (1912-1987), Desenho (Design), 1956. Ink on paper, 49.3 x 49.2

cm. São Paulo:

Museu de Arte Contemporânea, USP. Fig. 9: Judith

Lauand (b. 1922), Variação em curvas

(Variation in Curves), 1956. Enamel on eucatex, 60 x 60 cm. Fig. 10: Alexandre Wollner (b.

1928), Composição em triângulos

(Composition in Triangles), 1953. Enamel on duratex, 61 x 61 cm.

[Remade in 1977, after original in coll. Max Bill.] Fig. 11: Alfredo Volpi

(1896-1988), Xadres branco e vermelho (White and Red

Checkerboard), 1956. Tempera[?] on canvas, 53 x 100 cm. São Paulo: Coll. João Marino. Fig. 12: Mauricio Nogueira Lima,

Triângulo espiral (Spiral Triangle), 1956. Paint on eucatex, 60

x 60cm Fig. 13: Luiz Sacilotto, Concreção 5624, 1956. Oil on aluminum, 36.5 x 60 x 0.4 cm. Coll.

Renata Feffer. Fig. 14: Waldemar Cordeiro, Idéia

visível (Visible Idea), 1957.¨Tinta e massa s-compensado, 100 x 100

cm. São Paulo:

Pinacoteca do Estado. Fig. 15a: Augusto de Campos (b. 1931), “eis os

amantes” (1953/55) , from Solt, ed., Concrete Poetry, recto of inside

cover page. Fig. 15b: Augusto de Campos,

“here are the lovers,” trans. A. de Campos, Marcus Guimarães and Mary Ellen Solt ,

from Solt, ed., Concrete Poetry, verso of inside cover page. Fig. 16: Décio Pignatari (b. 1927), “um movimento,” from Noigandres 3,

1956; English version: Claus Clüver. Fig. 17: Augusto de Campos,

“terremoto” (1956), version published in Solt, ed., Concrete Poetry,

np. Fig. 18: Cover of Noigandres 4, 1958; design:

Hermelindo Fiaminghi. Fig. 19: Haroldo de Campos (1929–2003),

“nascemorre,” Noigandres 4, 1958. Fig. 20: Luiz Sacilotto, Concreção 6048, 1960. Oil on canvas, 60 x 120 cm. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do

Estado. Fig. 21: Ronaldo Azeredo (1937-2006), “ruasol,”,

Noigandres 4, 1958. Fig. 22: José Lino Grünewald

(1931–2000), “vai e vem” (1959), Anthologia Noigandres 5, p.

181. Fig. 23: Cover, antologia noigandres 5, 1962. Fig. 24: Alfredo Volpi, 1960, Coll. D. Pignatari. Fig. 25: Mauricio Nogueira Lima, 1953. Coll. Décio

Pignatari. Fig. 26: Hermelindo Fiaminghi, 1956. Coll. Décio

Pignatari. Fig. 27: Alfredo Volpi, two paintings. Coll. Ronaldo

Azeredo. Fig. 28: Luiz Sacilotto, 1958. Coll.

Ronaldo Azeredo. Fig. 29: Mauricio Nogueira Lima, 1960. Coll. Ronaldo

Azeredo. Fig. 30: Weissmann, Coluna,

1958. Painted iron, 280 x 110 x 75 cm. São Paulo: Museu de Arte

Contemporânea, USP. Photo: Claus Clüver, 1977. Fig. 31: Franz Weissmann, Trãs pontos (Three Points), 1958. Painted iron, 120 x 160 x

160 cm. Photo: Claus Clüver, 1977. Fig. 32: Installation shot,

“Projeto Construtivo Brasileiro na Arte (1950–1962)”, Rio de Janeiro,

Museu de Arte Moderna, 1977, with Franz Weissmann, Círculo inscrito

num quadrado (Circle Inscribed in a Square), 1958. Painted iron,

100 x 100 x 100 cm. Photo: Claus Clüver. Fig. 33: Amilcar de Castro

(1920–2002), steel sculpture displayed in front of the Palácio das

Artes in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, in 1976. Photo: Claus Clüver. Fig. 34: Amilcar de Castro,

steel sculptures displayed in the courtyard of the Palácio das Artes in

Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, in 1976. Photo: Claus Clüver.

(according to the list in ad, No. 20, December 1956)

Grupo “Ruptura,” São Paulo (since 1952):

* Geraldo de Barros (1923-1998)

* Lothar Charoux (1912-1987)

* Waldemar Cordeiro (1925-1973)

* Kazmer (Casimiro) Féjer (b.1922)

* Hermelindo Fiaminghi (1920-2004, joined in 1955)

Leopoldo Haar (1910-1954)

* Judith Lauand (b.1922, joined later)

* Maurício Nogueira Lima (1930-1999; joined in 1953)

* Luís Sacilotto (1924-2003)

Anatol Wladyslaw (1913–2004)

(gave up Concrete art in 1955)

Associated with the group:

Carlos do Val [in 1955)

Antonio Maluf (b. 1926)

* Alfredo Volpi (1896-1988)

* Alexandre Wollner (b. 1928)

Grupo “Frente,” Rio de Janeiro (since 1952):

Eric Baruch (joined in 1955)

* Aluísio Carvão

* Lygia Clark (1920-1988)

* João José da Silva Costa

Vincent Ibberson

* Rubem Mauro Ludolf

* César Oiticica (b. 1939?)

* Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980)

Abraham Palatnik (joined in 1955)

Lygia Pape (1929-2004)

Ivan Serpa

Elisa Martims da Silveira

* Décio Vieira

* Franz Weissmann (1911-2005)

Associated with the group:

* Amilcar de Castro (1920-2002)

Willys de Castro (1926-1988)

* Participated in n the “National Exhibition of Concrete Art,” 1956/57 Grupo “Noigandres”, S?o Paulo (since 1952)

* Augusto de Campos (b. 1931)

* Haroldo de Campos (1929-2003)

* Décio Pignatari (b. 1927)

Associated with the “Noigandres” group:

Edgard Braga (1897-1985)

José Paulo Paes (1926-1998)

Pedro Xisto (1901-1987)

From Rio de Janeiro

* Ronaldo Azeredo (1937-2006)

(joined “Noigandres” in 1956)

* Ferreira Gullar (b. 1930)

* Wlademir Dias Pino (b. 1927)

Not exhibiting:

José Lino Grünewald (1931-2000)

(joined “Noigandres” in 1958)

(2).“Projeto Construtivo

Brasileiro na Arte (1950–1962),” Rio de Janeiro: Museu de Arte Moderna;

São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado 1977.

(3). In the “Casa das

Rosas,” Avenida Paulista,

(4). Memorial exhibition “Arte Concreta Paulista”

at Centro Universitário Maria Antônia da USP, one section of which was

an attempt to reconstruct the “exposição do grupo ruptura no museu de

arte moderna de são paulo 1952". Catalogues: Arte

Concreta Paulista. 5 vols.

(7). Unless otherwise

noted, all translations are my own. The announcement of the exhibition

has been reproduced repeatedly, most recently in Pérez-Barreiro, ed., The

Geometry of Hope, 45. The reception of the program is documented in

Bandeira, org., Arte Concreta Paulista, 46–51.

(8). The images reproduced here are based on

slides I took from the originals, the majority at the 1977 exhibition

“Projeto Construtivo Brasileiro na Arte (1950–1962)” in Rio de Janeiro,

others in the homes of the Noigandres poets, or from documents in

my collection.

(9). Very

perceptively analyzed by Gabriel Pérez-Barreira in The Geometry of

Hope, pp. 128–130 (fig. 16); the design has been reproduced on the

front of the catalogue’s hard-cover edition as a shape embossed on

the uniformly blue cover (replacing the black-white contrast of the

original with a figure-ground relationship).

(10). I have

analyzed this painting more fully in Clüver, “Brazilian Concrete,”

208–09.

(11).This is the title listed in the

exhibition catalogue projeto construtivo brasileiro na arte (1950–1962), 14 (where the date is

given as 1953, apparently erroneously). In Cabral and Rezende, eds, Hermelindo

Fiaminghi, the painting is listed as Círculos Concêntricos e

Alternados, dated 1958 But the painting was included in the

1956/57 exhibit; a black and grey version of the design was featured in

ad, the exhibition catalogue, entitled “movimento alternado”

(n.p.).

(12). I have not

been in a position to follow up on possible changes in ownership since

my 1977 visit in the home of Ronaldo Azeredo.

(13). Sacilotto

called all of his works at that time “Concretions”, which he dated by

year and numbered.

(14). The slogan on the back of the invitation to the

1952 exhibit of Grupo Ruptura (reproduced in Amaral, org., Arte

Construtiva no Brasil 287).

(15). Another

version from 1956, smaller and using different materials (acrylic

on masonite), is reproduced in Pérez-Barreira, ed., The

Geometry of Hope fig. 24, accompanied by an extended analysis by

Erin Aldana, pp. 148, 150.

(16). Mario

Pedrosa, “Paulistas e Cariocas,” 136.

(17). Gullar,

“Manifesto Neoconcreto,” Jornal do Brasil (

(18). Schoenberg’s

idea that by changing instrumental or tone color one could produce an

effect analogous to the melody achieved by changing pitches was

developed more rigorously by Webern in his minimalist compositions.

(19). Augusto had

circulated them among friends as typewritten copies produced by using

colored carbon paper, at the suggestion of Geraldo de Barros (Augusto

de Campos, Interview).

(20). The original can be accessed at

http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/poemas.htm

(21).First published

in 1968 as a topical double issue of Artes Hispanicas / Hispanic

Arts (1.3-4).

(22). “terremoto”

appeared in Antologia Noigandres 5 as an unpublished poem. For

a very detailed analysis of this poem see Clüver, “Augusto de Campos’

‘terremoto’.”

(23). H. de

Campos had introduced the concept of the “open work of art” with regard

to structure and use of materials and the activity of the reader in

1955 (“A Obra de Arte Aberta”), long before Umberto Eco.

(24). “É claro

que certas características da nova poesia foram levadas por nós até o

limite, caso de lemas e temas polémicos como o da “matemática da

composição” e do “poema, objeto útil”. Acho, porém, que essa

radicalidade foi necessária diante da autocomplacência e do

sentimentalismo dominantes em nosso meio. Eu via no “racionalismo sensível” que

sustentávamos o ideário da poesia mesma: chegar a produções às

quais não se pudesse substituir uma palavra, uma letra, deslocar uma

parcela do texto sem que o poema desmoronasse — algo que é afinal a

meta de todos os poetas.” Augusto

de Campos, Interview, 16 Sept. 2006.

(25). See

Clüver, “Concrete Poetry: Critical Perspectives,” 271–72. – Like so

many of these ideograms, “nascemorre” is built entirely on a linguistic

peculiarity (in Portuguese, “nascer” and “morrer” are active verbs, and

personal pronouns are not needed) and on a spelling accident: the two

verb forms have the same number of letters. Moreover, the final sound

of “nasce” happens to equal “se,” and the “re” at the end of “morre”

takes on a function of its own.

(26). For an examination of the way the Noigandres

poets theorized different stages of isomorphism in their work see

Clüver, “Iconicidade.”

(28).These titles may

be part of the polemical opposition of Neoconcretism to Concretism. In

the catalogue of the 1977 “Projeto brasileiro constructive” exhibit the

work is listed as in the caption. However, Salzstein (90–91) captions

the work pictured as Coluna neoconcreta (196 x 76 x 52 cm),

MAC, USP; Ribeiro, opposes pp. 28 and 29 a photo of Coluna

Concretista (1952–53) with two photos of Coluna Neoconcretista

(1958–78, 140 x 50 x 50 cm, no location). In the MAC’s 1973 Catálogo

Gerald as Obras the sculpture shown on plate 147 is listed as Tôrre

(Tower; 1957, 169 X 62.7X 37.2 CM). Catalogues of 1988 (Amaral, Perfil)

and 1990 (O Museu) list no holdings of a Weissmann work.(but I saw the Coluna there in 1996).

(29). For

instance, Haroldo’s poem “mais e menos” was a response to Mondrian’s Plus

and Minus; his poem “branco”, which I discussed long ago as an

intersemiotic transposition of a Mondrian painting such as Composition

in Black, White and Red (1936; see Clüver, “On Intersemiotic

Transposition”), turns out to have been conceived as an homage to

Malevich.

(30). Cf.

Clüver, “The ‘Ruptura’ Proclaimed by

(31). One of the most important is the expansive

catalogue Poésure et Peintrie: «d'un art, l'autre», org. by

Bernard Blistène and Véronique Legrand, accompanying the exhibit of

intermedial poetry held in 1993 in Marseille.

(32). See esp.

Amaral, Arte Construtiva no Brasil (1998), with an extensive

bibliography.

(33). See Ana

Maria Belluzo, Waldemar Cordeiro: Uma aventura da razão (1986);

Isabella Cabral and M. A. Amaral Rezende, Hermelindo Fiaminghi

(1998); Ronaldo Brito, Amilcar de Castro (2001); Enock

Sacramento, Sacilotto (2001); Sônia Salzstein, Franz

Weissmann (2001); Helouise Costa, curator. Waldemar Cordeiro:

A Ruptura

(34). See

Amaral, ed.. Projeto Construtivo

Brasileiro na Arte (1977); Arte Concreta Paulista (2002) –

one of the 5 volumes is dedicated to Grupo Noigandres, curated

by Lenora de Barros and João Bandeira.

Concreta ‘56: a raiz da forma_ [ital.]. Exhibition catalogue, Museu de Arte Moderna, 26 September – 10 December, 2006.

São Paulo: Museu de Arte Moderna, 2006.