Transgressing

Limits: Belli’s El taller de las mariposas

University of

Gioconda Belli (1948)

is internationally known for her feminist poetry and fiction for

adults. Her one story for children, El Taller de las

Mariposas (The Butterfly Workshop), originally published in a

German edition in 1994, came out in

Few of Belli’s critics,

however, are even aware that she has published a children’s book. Of

the sixty-some critical articles on Belli’s corpus listed since

In Belli’s version of the creation myth,(2) all living things, animals and plants are invented by the “Diseñadores de Todas las Cosas” [Designers of All Things] who are divided into various workshops. Strict rules governing the cosmos guide the Designers and prohibit them from mixing the animals of the Animal Realm with the flowers, fruits and plants of the Vegetable Realm. Odaer, a young designer in the Insect Workshop (and Belli’s only male protagonist in her entire narrative corpus), feels the rule is too restrictive and becomes obsessed with how to make an insect beautiful, that is, how to achieve artistic perfection without contradicting the system or breaking the rules of creation. The key to his success lies in the possibilities of the imagination:

Gioconda Belli plantea que la esperanza debe

venir de la imaginación. Mientras no se pierda la fe en la capacidad de

imaginar mundos diferentes, va a poder existir el mundo de la utopía

(López Astudillo 107).

[Gioconda Belli proposes that hope should come from the imagination. While faith is not lost in the capacity to imagine different worlds, utopia will be able to exist].

Odaer, who parodies the image of the brooding, solitary, revolutionary artist, insists on searching for an idealized, utopian beauty. Specifically, he wants to mix the beauty of a flower with that of a bird, a combination that would be strictly prohibited under the current system. After many attempts and failures to achieve this dream, Odaer finally sees the shadow of a hummingbird reflected on the surface of a pond, reflecting the reds and blues of the sunset. In an epiphany, he realizes he has found his design for the butterfly.

This story on its literal level is transparent enough for children anywhere to grasp—European or Latin American, German, Spanish, or English-speaking. Belli’s fable, complete with a moral interwoven in the text (“El secreto estaba en no cansarse nunca de soñar” (40) [The secret was never to tire of dreaming]), clearly emphasizes Belli’s belief in the primacy of the imagination, the value of pursuing a goal, the virtue of persistence, and the conviction that dreams can become realities even under adverse circumstances.

While Belli emphasizes and encourages the role of imagination in the act of creation, she makes it quite clear to her children/readers that there are also limits that must be respected. The laws of creation in Belli’s cosmology are not arbitrary, but symbolize the limitations that we all face, whether natural or imposed, by our very human condition. The challenge for the child/artist, then, is to create within certain boundaries. Belli, like Sor Juana, believes that the ultimate value lies in the attempt even when the final product may be virtually unattainable:

. . .el poder de lo utópico se encuentra

precisamente en la expresión de su deseo y en su activa búsqueda aun

cuando se esté conciente de la imposibilidad de su materialización.(3)

. . .the power of utopia is found precisely in the expression of its desire and the active search for it even when one is conscious of the impossibility of its materialization.

Less visible or audible, especially to her children readers, are Belli’s multiple subtexts that merge to form a polyphonic discourse. These partially erased narratives hidden in the form of a palimpsest, address some of Belli’s ongoing concerns — political, theological, sociological, and artistic. The narrator’s insistent probing of the childlike question: why? — (why can’t I do that?) — reveals the frustration produced by the imposition of limits and voices the basic question at the heart of all change, invention, paradigmatic shift, or new vision. It is not surprising, then, that beneath Belli’s literal text we can identify other texts: a story of revolutionary struggle, a reinscription of the Biblical myth of creation, a deconstruction of gender and racial stereotypes, and ultimately a theory of art.

The political subtext

of this story is in many ways autobiographical (as is much of Belli’s

work) and deals with the author’s own psychological and personal

struggles to come to grips with her participation in the Sandinista

revolution in the 1970s. As a member of an upper-class family in

Odaer and his non-conformist group are nothing less than Romantic rebels. They work in secret against the existing order and disagree with the limitations and restrictions that have been imposed upon them. They have a dream and never give up, despite setbacks. Furthermore, Odaer sees his dream, not in personal terms, but as a goal for the general good: “Me siento responsable por hacerla más bella para los demás” (14); that is, he feels responsible for making life more beautiful for others. Ultimately, the group is successful, not because they have rebelled outright, but because they have approached their circumstances from a new perspective, synthesizing and merging apparent differences to produce a new and unique creation.

Odaer’s effort to keep

his dream alive, therefore, can be read as a simplified parallel to the

decade’s long Sandinista struggle. The existential implications of his

persistence mirror the philosophy of commitment shared by

One has to be careful not to take the Sandinista analogy too far, however. While Belli clearly celebrates the Sandinista vision and goals, she seems to have reevaluated their methods “and the permanence of machista rhetoric within Sandinismo” (Rhoden 89), particularly once they seized governmental control. In fact, Belli ultimately separated herself from the Frente Sandinista citing its authoritarian hierarchy and calling for a democratization of its structure to allow for the full participation of all of its leaders (López Astudillo). The story of Odaer and his friends marks this move away from the revolutionary politics of the FSLN. Fernández Carballo, in his graduate thesis on Belli’s novel Waslala, calls El taller de las mariposas an allegory of utopia: “plantea la utopía que ha de contribuir a la belleza y la armonía del ser humano, pero sin que ella subvierta el orden existente, más aún, que tenga la aprobación de dicho orden” (25) [she posits a utopia that would contribute to the beauty and the harmony of human life, but that would not subvert the existing order; even more, a utopia that would have the approval of that order]. Politically, therefore, Belli seems more conservative in this book. At the very least, Odaer’s struggle marks a change in her approach from direct conflict and confrontation to a more imaginative and consensual approach to change and creativity.

On a theological level, Belli has created a feminist alternative to the Biblical version of creation. In her cosmology, although Odaer, like Adam, is male, the highest power, the maximum force and authority in the universe, the controller of all knowledge, is female—She who controls all knowledge. Belli’s book of poems De la Costilla de Eva (1983) also rethinks the traditional patriarchal discourse of creation in much the same way. According to Kathleen March “To see Eve as Creator does not imply a rejection or humorous dismissal of the male sex. . .but rather…a return to and a focussing (sic) upon, a matricentric world view such as that of antiquity” (246).

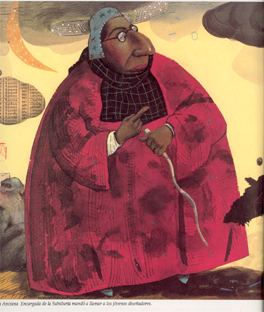

This gender shift in our traditional patriarchal conceptions about God is merely the first and most obvious transgression against orthodoxy in this tale. The illustrations that accompany the text insinuate a host of additional subversions and transgressions far more radical and heretical. First, the Ancient Woman in Charge of Knowledge is also a person of color. Her skin is dark and her exaggerated facial features form a caricature of a native American/Amerindian. More disturbing, however, are her red dress, the serpent-like cane she carries, and her phallic index finger, which she is always pointing. This sexually ambiguous image is consistent, however, with the archetype of the Great Mother: “Mother Earth, origin of all, had both male and female attributes, her symbols such as the moon, the bull, and the serpent” (March 255).

Traditional

connotations associated with race (black/indigenous), the red dress

(symbol of sexual transgression), and the serpent (Biblical symbol of

evil) are sub(in)verted in their association with the Ancient Woman.

Like God, her Christian counterpart,

While the symbolic sexual overtones in the illustrations clearly work to subvert patriarchal discourse, they also serve to reinforce La Anciana’s authoritative stature as an ontologically complete and independent being, in charge of her own sexuality, indicating, directing, and delegating with that outstretched finger. Like many of the women in Belli’s other novels, she is “sexually self-assured” (Rhoden 81). Yet, certainly she is an unconventional authority. Unlike the visionary image that Christianity projects of omniscience, Belli’s keeper of knowledge stares out from behind a pair of thick glasses, more reminiscent of an intellectual, than a Christian God who sees every sparrow fall. Furthermore, contrary to the Christian tradition of Genesis, where God omnipotent creates the world by Himself, Belli’s Ancient Woman delegates creation to the various workshops. This idea of creation as a product of teamwork fits the ideals of the early FSLN. Furthermore, the image of creation as the product of hard work and physical compromise is consistent with Belli’s poetry where she portrays God with hammer and drill in hand:

Todo lo creó suavemente

A martillazos de soplidos

Y taladrazos de amor (“Y Dios me

hizo mujer”)

[He created everything softly/Hammering with puffs of air/And drilling with love] (translation mine).

The Ancient Woman’s managerial style also contradicts the patriarchal autocracy of the Church (and what turned out to be a similar structure within the Sandinista Party). Her decisions are not top down, but consensual; when Odaer asks for a new workshop dedicated specifically to the design of butterflies, he must convince the other Designers of All Things, not just the Ancient Woman.

Finally, a more subtle

transgression: the work week is reduced to five days, rather than the

biblical six with rest on the seventh day. Work is continuous and

ongoing. There is no rest for dreamers. In Belli’s system, even when

Odaer sits by the pond, he is overwhelmed by thought and desire: “No

podré descansar hasta que no pueda diseñar algo que sea tan

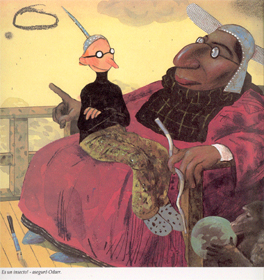

Belli’s Anciana is truly an ambiguous and paradoxical figure. The narrator calls her the boss — la jefa de los Diseñadores de Todas las Cosas. Her job, it would seem, is to maintain harmony in the universe. Consequently, Odaer and his friends’ insistence on thinking of all the things they could invent if the rules were different concerns her: “se preocupó y decidió que era necesario hacer algo que impidiera que las ideas de Odaer se hicieran populares, ya que ponían en peligro la armonía de la creación”(7) [she worried and decided it was necessary to do something to prevent Odaer’s ideas from becoming popular, since they could endanger the harmony of creation]. From a political standpoint, this kind of justification of the status quo sounds like a tyrannical Somoza-type railing against the ideas of the Sandinista National Liberation Front. From a theological standpoint, it smacks of the rigid control of the Catholic Church. Yet, the boss is not depicted as a tyrant or an autocrat as the text progresses, and visually, she is the subversion of a conventional leader. Her gender, her color, her exaggerated Mayan nose and high cheekbones (salient racial features of the New World Indians), her obesity and poor vision, form a composite picture that resists and subverts the Eurocentric concept of beauty. She is portrayed more as the wise old grandmother figure than a goddess. It is significant, therefore, that in one picture Odaer is sitting on her lap.

Political and religious parallels aside for a moment, the more important issue under discussion in this story would seem to be the concept of beauty: what it is and what it does or should do. In this sense the Ancient Woman in charge of knowledge seems to have rightly come by her position. While she demotes Odaer and his group to the dusty Insect Workshop to keep them out of trouble, she argues against Odaer’s conventional complaint that insects are not beautiful. “Y quién dice que no pueden serlo. . .Háganlos bellos. De ustedes depende. Tienen toda la libertad para diseñarlos como mejor les parezca”(7) [And who says they can’t be? Make them beautiful. It depends on you. You have complete freedom to design them however you think best]. Although Odaer considers that the rule against mixing plants and animals is too restrictive, he paradoxically restricts his own conception of beauty by conventional ideas, conventions that the Anciana both contradicts verbally and subverts through her visual presence. Her advice to the young designer is not only aesthetic, however; it can also be read on a theological and political level as well:

En tu búsqueda del diseño perfecto, puedes crear monstruos. Tu afán de hacer la vida más agradable y bella, puede resultar, si no eres cuidadoso, en dolor y miedo para otras creaturas de la naturaleza. (10)

In your search for the perfect design, you can create monsters. Your urge to make life better and more beautiful, if you’re not careful, can result in pain and fear for other creatures in nature.

Belli’s critique here

of the Sandinista government is hardly subtle. She makes an

incontrovertible distinction between a dream and an obsession. An

admirable goal, she seems to say, whether political, theological, or

artistic, still must carefully monitor its means: “La búsqueda de la

belleza y de la perfección está llena de tropiezos. Muchos se han

perdido en el camino”(11) [The search for beauty and perfection is full

of obstacles. Many have gotten lost along the way]. Such a search, she

implies, is tantamount to the search for knowledge in Christian

theology where so many with lofty goals, from Satan to Adam, have

fallen. Equally, the Anciana’s remark may be read as a comment on

revolutions gone wrong, from

In addition to the

political and theological nuances of Belli’s story, therefore, the

underlying dialogue about the nature of beauty and art and the role of

the artist in society is at issue. Belli joins this

discussion-in-progress that begins with the pre-Columbian Amerindian

cultures of the Isthmus and reaches its zenith in

Para ella, el reto más grande de la creación es

encontrar en este momento de la historia (cualquiera que sea). . .cómo

se puede insertar el escritor o escritora con su trabajo creativo y

mantener viva la esperanza, incluso convertirse en un creador o

creadora de posibilidades (López Astudillo 106).

[For her, the biggest challenge in creation is to find in this historical moment (whatever it might be). . .how the writer can intervene with his or her creative work to maintain hope alive, and even to convert himself or herself into a creator of possibilities].

Odaer, when he talks to those around him, merely sets the stage for Belli to talk back to the past, engaging in a diachronic dialogue about the meaning of beauty and the purpose of art. At one point a rock asks Odaer “Pero, cuál es el sentido de una flor?. . .Se marchita muy pronto y muere” (21) [But what is the meaning of a flower? It soon wilts and dies]. It is significant that in Belli’s story the rocks and the dogs talk just as they do in the Mayan creation myth recounted in the Popol Vuh. The fact that the rock asks about the meaning of a flower can be seen either as ironic, from a Western perspective, or as completely consistent with an Amerindian perspective that holds that all things, whether animate or inanimate, have a spirit or soul, and as such are all connected. In this way, Belli’s magically real world of Western children’s literature (where animals, plants, and rocks routinely talk and have feelings) converges with the cosmological vision of the Mayan communities where man and the natural world are interrelated and interdependent. This notion of interconnectedness is not limited to Belli’s story for children, however; literary analyses of the new ecocritical school (4) have begun to study the role of nature in Belli’s other work.

Odaer’s response to the rock’s question is ambivalent: it both agrees and disagrees with Dario’s defense of art for art’s sake: “Se hace fruto…Pero además es bella. Lo bello no se puede explicar, se siente” (21) [It bears fruit... But in addition, it is beautiful. Beauty cannot be explained; one feels it]. Certainly, Darío would agree with Odaer and Belli’s articulation of art as felt experience, but he might be less willing to concede that art or beauty bears fruit and that this function gives art meaning. Belli, in a recent interview, insists, however, on this functional aspect of art, particularly on its critical role; she is fully conscious of her political commitment: “siguiendo un poco la tradición latinoamericana de participación política de los escritores” (Dobles 6) [following a bit in the Latin American tradition of political participation of its writers] and cites Darío in her explanation about the role of the artist:

De cierta manera el poeta es profeta, como

dicen, y entonces esa calidad, esa dimensión de la poesía que le

atribuye la gente espontáneamente por la historia que tenemos, por

Rubén Darío, por lo que sea, de alguna manera también es una

responsabilidad de participación para mí, de ser una voz crítica, de no

dejar de hacer análisis crítico, de hacer conciencia crítica de la

sociedad. (Dobles 6)

[In a certain way the poet is a prophet, as they say, and so that quality, that dimension of poetry that people attribute to spontaneity because of the history we have, because of Rubén Darío, because of whatever, in a way also indicates a responsibility to participate for me, to be a critical voice, never to stop making critical analysis, to make conscious criticism of society.]

Moreover, art as felt experience implies an aesthetic problem concerning the kinds of feelings art projects or provokes in its audience. Belli parodies the problem in a short dialogue between a lightning bolt, a serpent, and Odaer:

La belleza es como cuando yo aparezco en el cielo e

ilumino todo lo que toco-dijo el rayo.

–Pero tú das miedo-dijo la serpiente.

–Mira quién habla-respondió el rayo. (21)

“Beauty is like when I appear in the sky and illuminate everything I touch,” said the lightening bolt.

“But you’re scary,” said the serpent.

“Look who’s talking,” responded the lightning bolt.

Certainly Darío would be more inclined to agree with the lightning bolt, that beauty illuminates everything it touches, for beauty, Darío thought, need only exist. But Odaer’s response to this humorous exchange is deadly serious: “Yo quiero algo que dé felicidad” (21) [I want something that produces happiness]. Odaer’s conception of art, and we can logically assume Belli speaks through him, ultimately agrees with the precepts of beauty and idealism that underpin Darío and the Latin American Modernist movement: “Creo en ese poder de la palabra, extraordinario, de la palabra que nos une a todos; ser parte de esa red” (Dobles 6) [I believe in that power of the word, extraordinary, of the word that unites us all; to be part of that network].

Perhaps, with Odaer’s insistence on creating beauty that imparts happiness, we have the clearest distinction in the debate over the differences between children’s literature and adult literature. Certainly, if the production of happiness is the sole criteria for art, much of the adult canon would fail to qualify. But the happily-ever-after convention in children’s literature is a firm component of reader expectation, and one that Belli adheres to in this story. Art is fragile, as the wind and the volcanoes point out to Odaer; beauty can be damaged and destroyed, but Odaer counters that it always returns; it never gives up. Thus, art for Belli falls within the Mayan tradition of the natural cycles of rebirth and regeneration as well as Darío’s ideal of art as the ideal and the essence of human dreams and imagination.

Even though “a nadie parece importarle que no exista eso que tu quieres diseñar” (14) [no one seems to care that what you want to create doesn’t exist], Odaer firmly believes that the world will be a better place because of his creation. Although he has chafed at the limitations imposed on his artistic potential, he has played within the rules; he has not changed them. Still, he has managed to find his own poetic voice. As Belli talks back to her artistic past, chafing at the limitations imposed by her aesthetic heritage and searching, like Odaer, for her own poetic voice, she inevitably returns to the literature that precedes her. After the decades long political struggle in Nicaragua and elsewhere in Latin America, after all the testimonios and revolutionary poetry produced in Central America as the result of the low intensity wars of the 1970s and 80s, Belli ultimately returns to Dario in this story for children of all ages and concedes that beauty is its own reward.

Notes

(1).

Actually, one article refers to the work as part of her narrative

corpus but calls it a book of short stories, which it is not (López

Astudillo 106). The entry on Belli in Gale’s Dictionary of

Literary Biography (Preble-Niemi) dedicates two sentences to the

book and completely misrepresents the plot, claiming that the story

“tells of a laboratory worker who whimsically crosses a flower and an

insect to create the butterfly.” The entire point of the story is that

the protagonist, who is not a laboratory worker but a designer in

Belli’s recreation of the cosmos, is not allowed to cross elements of

the vegetable realm (a flower) with elements of the animal realm; and

the animal in question is not an insect but a hummingbird. The point

is: neither of these critics even bothered to read the story, assuming,

no doubt, that a child’s book is neither relevant to nor worthy of

comment in an overview of Belli’s narrative corpus.

(2).

Rewriting the myth of creation is a recurrent theme in Belli’s work.

(3).

Moyano (22) is talking here about Belli’s futuristic novel Waslala

(written at the same time as Belli’s children’s book), which

presents the loss of utopia and the future of Latin America as “grandes

extensiones de tierra donde prevalecen las guerras y el narcotráfico,

el caos en suma, y cuyo fin será el convertirse en el basurero de la

tecnología y el progreso del Norte” [large extensions of land where

wars and drug trafficking prevail, in sum

chaos, and whose destiny is to become the trash heap for the technology

and progress of the North].

(4).

See Fayes, for example, who quotes Paula Gunn Allen in "The Sacred

Hoop: A Contemporary Perspective," to explain that “indigenous peoples

understand life as a ‘sacred hoop,’ which is ‘the concept of a singular

unity that is dynamic and encompassing, including all that is contained

in its most essential aspect, that of life--that is, dynamic and aware,

partaking as it does in the life of the All Spirit and contributing as

it does to the continuing of life of that same Great Mystery.’ An

important consequence of these beliefs is that ‘tribal people allow all

animals, vegetables, and minerals (the entire biota, in short) the same

or even greater privilege than humans’ (243). This attitude towards

nature is characteristic not only of North American Indian cultures but

also of the indigenous peoples of

Works Cited

Belli, Gioconda. De la costilla de

Eva. Managua: Editorial Nueva Nicaragua, 1987.

Belli, Gioconda. El taller de las

mariposas. Managua: Ananá Ediciones Centroamericanas, 1996.

Dobles, Aurelia. “Gioconda Belli: Vocera de la emoción y la razón.” La Nación. Suplemento Ancora. (18 February 2007): 6-7.

Fayes,

Helene. “The Revolutionary Empowerment of Nature in Belli’s The

Inhabited Woman.” Mosaic 38.2 (2005): 95-111.

Fernández Carballo, Rodolfo. “Utopía y

desencantos en la construcción de una comunidad imaginada: Waslala

memorial del futuro de Gioconda Belli.” M.A. Thesis. U of Costa

Rica, 2006.

López Astudillo, Sandra Elisabeth. “Gioconda

Belli: con palabra de mujer.” Encuentro 35.65

(2003):102-129.

March,

Kathleen N. “Gioconda Belli: The Erotic Politics of the Great Mother.” Monographic Review/Revista

Monográfica 6 (1990): 245-257.

Moyano, Pilar. “Utopía/Distopía: La

desmitificación de la revolución sandinista en la narrativa de Gioconda

Belli.” Ixquic: Revista Hispánica Internacional de

Análisis y Creación 4 (February 2003): 16-24.

Rhoden, Laura Barbas. “The Quest for the Mother in the Novels of Gioconda Belli.” Letras Femeninas. 27 (2000): 81-97.