Augusto de Campos, Digital Poetry, and the

Anthropophagic Imperative

Chris Funkhouser

New Jersey Institute of Technology

When Pero Afonso de

Sardinha arrived on the shores of

Anthropophagy (or cannibalism) was the name assigned to this unusual, iconoclastic, and somewhat obscure creative philosophy, a concept announced by, and exemplified in, Oswald de Andrade’s “Anthropophagy Manifesto” (1928), which proclaims “I am only interested in that which is not my own” (65).(1) External texts and idioms become grist for the anthropophagist’s mill, a trait reflected in Oswald’s short poems “Biblioteca Nacional” (partially composed of juxtaposed document titles, e.g., “Brazilian Code of Civil Law/How to Win the Lottery/Public Speaking for Everyone/The Pole in Flames) and “Advertisement” (which adopts the language of advertising copy, e.g., “All women—deal with Mr. Fagundes/sole distributor/in the United States of Brazil”) (Bishop 11, 13). While numerous poets and artists were profoundly motivated by anthropophagy, this presentation divulges the underlying principles and impact of the concept as it relates to poetic works by Augusto de Campos, who has tapped into aspects of Oswald’s idea as a resource and rationale throughout his career.(2) Connections between anthropophagy and digital poetry, an emerging genre known for its synthesis of fragments (which Augusto has also practiced for many years), will also be introduced.

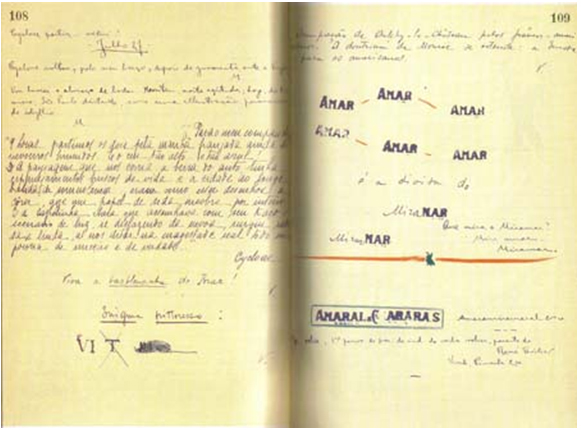

Augusto explains in a

2005 interview, “Oswald made a distinction between anthropophagy and

pure cannibalism—by hunger or by greed—from ritual anthropophagy.

Ritual anthropophagy is a branch of anthropophagy in which the cannibal

eats his enemy not for greed or for anger but to inherit the qualities

of his enemy. The metaphorical, and also in certain aspects

philosophical, idea of cultural anthropophagy Oswald promoted was the

idea of cannibalizing the high culture from Europe, with the results

that one could acquire, or could have from this devouration, and could

then construct something really new out of this development” (Interview

2005). An excellent example of how Oswald’s practice incorporated these

premises is found in a diagram included in a page of O

perfeito cozinheiro das

This book contains

writing as well as significant visual attributes, including drawings

and, as in Fig. 1, Oswald’s use of rubber stamps. O

perfeito cozinheiro das almas deste mundo, a collaboration similar

in style to the surrealist practice of the “exquisite corpse,” was

started by Oswald but filled with contributions by anyone who visited

or participated in salons held at Oswald’s

Anthropophagy was also influenced by Futurism, and proposed that creative potential is reached through a skepticism of organizational systems which include, as Caetano Veloso remarks in Tropical Truth, “nationality, history, language” (155). An anthropophagic text devours other texts and icons to create a form of expression that is “at once loose and dense and extraordinarily concentrated” (155). Discovery and re-discovery of meaning is reached through the cannibalization of texts, which may then establish alternative perspectives on cultural or personal subjects taken up by authors in textual composition, re-composition, and composting (as seen in the examples of Oswald’s poems above). Artists are free to reshape external influence, writes Rodrigo Nunes, “to its own ends, without allowing itself to become imprisoned by anything that might restrain its vitality” (n. pag.). CriticBernard Schütze has observed anthropophagy involves “an open process of dynamic transformations in which identity is never fixed but always open to transmutations,” which “produces a reservoir of heterogeneity” (n. pag.).

Although he was a crucial poet and thinker, Oswald was not always taken seriously by the Brazilian literati.(3) All of the Brazilian concrete poets were, however, aware of his theory of anthropophagy, became influenced by it, and to varying degrees promoted certain of its elements in order to “reclaim the origins of Brazilian modernism… and to reassert its international prospects” (Green). In the production of text, cultural and aesthetic matter is absorbed (like structures or techniques from other visual disciplines), and then formalistically pronounced in various ways by the concrete poets, including the many translations done by members of the group—famously described as transcreations by Haroldo de Campos. From a certain perspective, the habitual, steady flow of translations could be considered the most anthropophagic output of the concrete poets, even if the persevering dedication to invention of expression implemented via means of graphical apparatus is also convincing evidence of ritualistic practice. Replying to a recent inquiry about this matter, Augusto writes: “Our approach was not, physically, or say, dyonisiacally ritualistic…. We viewed Anthropophagy as an anthropologic metaphor, nurtured in Freud, Nietzsche, Lévy-Bruhl and Bachoffen (from whom he took the theory of ancient Matriarchy, that would have preceded Patriarchal society, associated with authoritarian monarchies and private propriety)…. The brainstorming in which we three, Decio, Haroldo, were engaged, in a Poundian way (“paideuma”, “the age demanded”), trying “to gather from the air a live tradition”, reading in several languages as only barbarians do to arrive at the selective choice MALLARMÉ-JOYCE-POUND=CUMMINGS was surely linked to the Oswaldian cultural ANTHROPOPHAGY” (Email 2006).

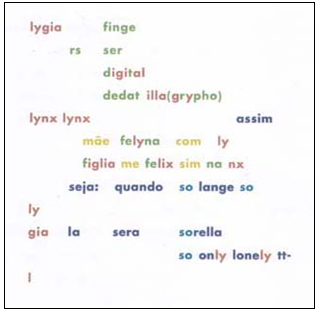

While this presentation exclusively focuses on Augusto’s work, the discussion could be widened and address works by Décio Pignatari (e.g., “Adieu, Mallarmé,” 1954) and other concrete poets, as well as historical figures previously mentioned (Bopp, Carvalho) and younger artists who practice with intent today. I’ll show examples of works from three different stages of Augusto’s non-electronic work, which indicate anthropophagy as an operative principle. The colored poems of “Poetamenos” series (1953), such as “lygia” [Fig. 2] are multicursal: crafted language leads the reader through various paths.

Vivavaia 71.

Visual information, like color, and typographically scripted presentation—tools inherited from visual and graphical artists—are a source of sustenance in these poems. Various emerging strands can be experienced in any order, and a viewer’s experience with the poem is defined by the way he or she reads it. Use of different colored texts, and implied sonic (echoic) attributes, give the impression that multiple texts are stitched into one shaped pronouncement with visual texture. In “Poetamenos” the impression is literal fact, as the author repurposes quotes borrowed from poems by Luís de Camões and others.(4) Further, in the prefatory note to “Poetamenos,” Augusto explains that he intended the series to be a representation of Webern’s concept of "klangfarbenmelodie" (tone-color-melody). Different states of emotion/intonation, used to pronounce the lyrical threads, are expressed in each of the colors. A correspondence between heretofore discrepant senses of “color” in music and graphics are established in these multi-sensory poems.

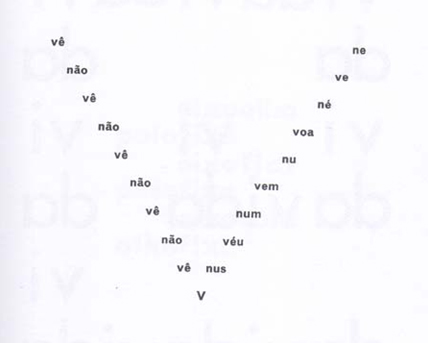

Although his stated technological desire for “Poetamenos” was not met (“but luminous display of film letters, wish we could have it”), Augusto surely achieves the effect of radiant presentation on the page (Vivavaia 65). The poem’s sonic attributes are significantly anthropophagic. Each of the three brief sections are discursively built on aural associations, beginning with the word “lygia,” follwed by echoic variations built with verbal fragments chosen by the poet. The poem is activated by this creative recycling reflected in the characters on the page and how we hear it. In subsequent works, like the “Novelo ovo” series (1954-1960), a shaped poem is composed with short words that at once sustain a dialog and present a compelling diagram, using words to form a letter (and a shape) rather than letters forming a word [Fig. 3].

While graphically less complex than “Poetamenos,” the work presents similar challenges for the reader, who will see first the overall shape and proceed to follow a path from there. The poem is at least partially anthropophagic because this macro- “v” propels the poem on multiple levels; it is unquestionably used by the poet to build form and content, reflecting “v” as versus (v.), verb (v.), and verse, coming to a point, from which the poem vectors out.

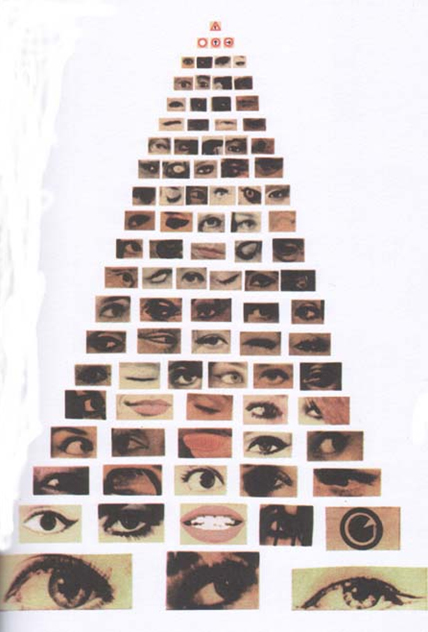

In Augusto’s mid-1960s “Popcrete” phase, incorporation of unrelated external influence and materials increases: images from fashion magazines and newspapers are blatantly dismembered to make unusual, calculated, and sometimes non-linguistic works.

In this example [Fig. 4], instead of interpreting what the language presented might mean, someone who encounters the work must “read” the assembled symbols, and crack a type of visual code in order to build comprehension. The anthropophagy is transformative: external icons—and the culture they are a part of—are re-shaped into something with an agenda unrelated to their initial purpose. A new context asserts the possibility, if not reality, of alternative planes of sight and multiplicity of perspective. Among the many curious aspects of this particular work are the four symbols at the top of the chart: three arrow keys inside circles, pointing to different directions, and an empty circle. This facet intimates if not forecasts interactivity: you can stop here or proceed in a different direction.

A more recent book, Não Poemas (2003), includes several “Profilogramas,” single-page poems that serve to transmit—through the visual language and textscape presented—rapid profiles, philosophical reflections on people who have made an impression on Augusto.(5)

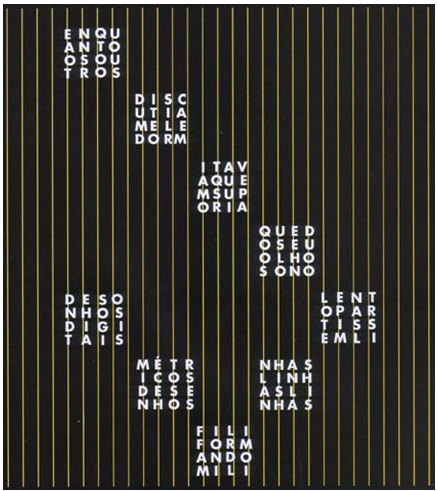

In “charoux” (1996) [Fig. 5], straight lines, box shapes, and hooks, which are icons and techniques found in images of Paulista painter Lothar Charoux, are overtly evident and used to provide shape and texture to Augusto’s poem. With non-trivial effort, words can be deciphered, although the tactics of reading most certainly differ from those used when poems are of standard delineation. The reader must (again) decide where to begin (possible starting points here would be either “De sonhos digitais…” [from digital dreams] or “Enquantos outros…” [while others]), and determine where words begin and end. The anthropophagic elements, while resolvable (after all we should recall this is a modernist proposition), present distinct dimensions and challenges: the graphical insistence and appropriation in these works complicate the poetry considerably.

Another section of Não Poemas, “Intraduções,” consists of transcreations

in which non-verbal techniques (in type or design), absent from the

originals, aim to produce iconic interpretations and interdisciplinary

dialogues.(6) Augusto reworks texts by

Khlebnikov, Stevens, Akhmatova, Bassho, Rilke, and others, applying

“calligrammic techniques in more refined graphic structures” (Email

2006). The following poem [Fig. 6], revisits and repurposes Bassho:

rã de bashô (1998) Não poemas 97.

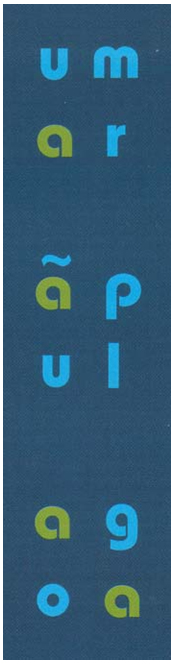

Clearly the overtly decipherable words in “rã de bashô”—uma, rã, pula, goa (the last of which is a neologism)—could only be an intimation or fragment of anything Bassho wrote.(7) Augusto, through use of coloration in the letter “a,” depicts a multidimensional text, where even more of a language puzzle is presented than in previous examples. Characters can be read horizontally and vertically; alternative linguistic recognition emerges through enjambement or collision. New words are proposed by the poet using a designer’s touch on the work.

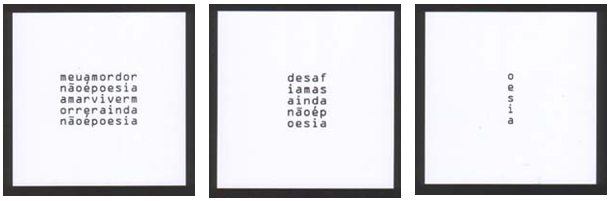

The book’s title poem “Não” begins as a block of text [Fig. 7], gradually consuming and compacting itself over ten pages to become a “no” poem—one that sends a message through an active relationship between word and page. The initial text is cannibalized, as is the “p” in “poesia” [Fig. 9] to illustrate process and result.

Figs.

7,

8, 9. Augusto de Campos, from Não. Não

poemas 21, 31, 39.

The technique recalls Lenora de Barros’s early video poem “Entes…Entes…” (“Beings…Beings…,” 1985), in which mirrored word forms are sequentially molded into different twenty line patterns, becoming gradually compressed into blocks.(8) In Barros’s and Augusto’s work, the viewer/reader is left to wonder what becomes of the poem—and why—as the line length compacts into fragments. The poets squeeze the verbal information to the edge of semantic recognition; yet, in both examples, the visual activity of the poem serves to enact the verbal content.

Digital

Poetry

Before proceeding to look at Augusto’s computer-based works, I want to pause to introduce briefly some perspectives on poetry enabled by digital media, which has been called e-poetry, computer poetry, cyberpoetry, and digital poetry.(9) Essentially these labels are used to describe a new genre of literary, visual, and sonic art launched by poets who began to experiment with computers in the late 1950s. Poets initially used computer programs by synthesizing a database and a series of instructions, in order to establish a work’s content and shape. By the mid-1960s, graphical and kinetic components emerged, rendering shaped language as poems on screens and as printouts. Since then, videographic and other types of kinetic poems have been produced using digital tools and techniques. Beginning in the 1980s, hypertext (mechanically interconnected non-linear texts) developed in sync with the increasing availability of personal computers. A few other experimental forms, like audio poetry and holographic poems, emerged as media technology advanced.

References to concrete poetry are far from uncommon in dialogues regarding the influence of literature on new media productions: concrete poetry has been cited as an influence on computer poems since the first two books on the subject appeared in the 1970s, Richard W. Bailey’s anthology Computer Poems (1973) and Carole Spearin McCauley’s monograph Computers & Creativity (1974). Bailey writes that in graphical computer poems, “concrete poetry is reflected with a computer mirror” (n. pag.). McCauley acknowledged in Computers and Creativity that computerized graphical poetry “resembles, or perhaps grew from…‘concrete poetry’” (115). More recent books on the subject, such as Loss Pequeño Glazier’s Digital Poetics (2002) and Brian Kim Stefans’s Fashionable Noise (2003), also discuss the relevance of concrete poetry to the development of digital poems.

The invention of the

computer is certainly one of the definitive moments of the past fifty

years. One of the foremost ways digital poetry is

anthropophagic is because it mints a literary concept via the

absorption of forms of expression and production that were not

previously related to digital technology. Poets courageously embraced

formidable machines, built for the progression of science and business;

their explorations are sometimes fruitful. Assimilation of texts and

language unrelated to computer operations, which results in the

reinvention of both language (through programming) and computers

(through making poems with them), has endowed digital poetry with a

type of autonomy, and numerous projects contain artistic qualities

worthy of circulation and study. The anthropophagy of early computer

poems generated by algorithmic equation reify modernism’s inscription

of tentative, nonlinear arrangements of text (use of randomized

elements, as in Dada, is sometimes employed). Instead of computing

equations and processing data, the computer is entrusted with creative

expression, giving the machines and programs a role in the negotiation

between author and language. Since 1959 text-generating programs that

process and permute databases of words into poems have been built by

poets. Mechanically consuming a text to project a new text is

unquestionably anthropophagic on an aesthetic register. The

anthropophagic analogy, in which perpetual digestion is a necessary

function, also corresponds to one of the profound observations on

hypertext and hypermedia, upon which contemporary identities for

digital poetry now rest. As Michael Joyce has observed, electronic text

almost always authoritatively “replaces itself” (rather than affix

itself)—a defining characteristic of digital poetry (Joyce 236). This

possibility invites the author to reconsider what an author is and

does—a far-reaching concept that permits poets to use previously

composed texts within new contexts.

Augusto

de

Campos’s electronic works

Another theme in Oswald’s project of anthropophagy was to imagine changing taboo into totem. Augusto, who began presenting poems on computers in the early 1980s, has always rejected the idea that technology is forbidden; in fact it is desired (and not to destructive ends). His engagement with computers as a poet was contrary to typical avant-garde methods at the time. As Marjorie Perloff observes in the early 1990s, “the most common response to what has been called the digital revolution has been simple rejection” (3); she explains that the consensus amongst most poets was that “technology…remains, quite simply, the enemy, the locus of commodification and reification against which a ‘genuine’ poetic discourse must react” (19). By now, a more realistic perspective generally acknowledges computer hardware and software are tools capable of presenting vibrant poetic works; Augusto has used them since the moment he was given access. As he stated in an interview with Roland Greene, “The virtual movement of the printed word, the typogram, is giving way to the real movement of the computerized word, the videogram, and to the typography of the electronic era. From static to cinematic poetry, which, combined with computerized sound resources, can raise the verbivocovisual structures preconceived by CP [concrete poets] to their most complete materialization” (Greene n. pag.).

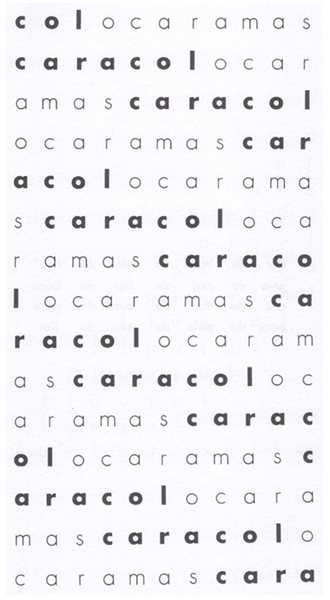

Several works on the Não Poemas CD-ROM (

Augusto’s “interpoem” “conversograms” directly fuses the voices of other artists with his own. This short piece, an “imaginary conversation” between Cesário Verde, Fernando Pessoa, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, ends playfully, with the faces of the three authors superimposed in an elegant portrait. [demonstration of CD “conversograms”] These poems display a type of feedback, digesting the other in order to invent; it is composition as a regurgative, recyclical process in which European subjects or other outside influences are transformed “into metaphorical objects of consumption,” worthy of being assimilated in the construction of an ongoing cultural project in the present (Rocha n. pag.).

These intertwining works, digested, are not only poetic but critical—Augusto is selective and purposeful, biting what he can, chewing on it to make something new. He samples characters and cultures that have influenced him, combines sound bytes and animations to assert the relevance of work, and adds his own material into the body of the poem. Within it, as in “Caoscage”—which predominantly features John Cage’s voice, picture, and words—Augusto not only intervenes with his own voice but has the power to control all aspects of the content included. In this piece a multistage, interactive narrative is presented, a reconstruction of, and synthesis with Cage that makes a statement about chaos. [demonstration of CD-ROM version of “Caoscage”] Describing the composition of this piece Augusto recalls he

took a musical cell of Boulez and united it with a Cagian fragment. So you cannot recognize what is Cage and what is Boulez. There are in a single musical cell. Sounds that appear when you interact with the image of that circle, the image of chaos, because Cage recalls the anecdote, the story of Kwang-Tse, so the seven signs that compound the face arrive at the end. When the face is completed, chaos appears and then Cage (Interview 2005).

Each of the “morphograms” on the CD use a similar technique, typically uniting in shorter bursts of expression two voices with a representative animation of the speaker’s facial profile. “Stein Pound” begins with a photograph of Gertrude Stein that becomes, before the user’s eyes, Ezra Pound, while the intermingling voices of the authors are heard. [demonstration of CD-ROM version of “Stein Pound”] “Joao Webern,” probably my favorite, fuses line drawing animations of the faces composers João Gilberto and Anton Webern while sounds composed by these artists are playing. [demonstration of CD-ROM version of “Joao Webern”] The sounds, while discrepant, are harmonious; we are introduced to audio and visual elements, notes and drawings, brought together as simultaneities. Different forms of nutrition feed the poem. The samples are played forward, backwards, and then forward again; a flow is apparent in the experience of the presentation, as is a sense the author is exploring the possibilities of feedback.

The “Clip poemas” from 2003 continue to explore the possibilities in merging kinetic text and processed spoken language. In the “Rever” section, there are new versions of “Cidade” (retitled “Cidadecitycité”) and “Ininstante”. Animated text and sound are the primary features. One work in particular, however, establishes a new appearance—perhaps more literal—of anthropophagic effect. “Sem-Saída” is laid out so that it presents itself then devours itself. At first, the overall visual structure of the poem is shown briefly as montage on the screen. Then the user drags the mouse to unveil the first line of text. In order to proceed through the piece, the viewer must visually dismantle (by erasure with the mouse) the text that has just appeared on the screen. [demonstration of CD-ROM version of “Sem-Saída;” see http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/clippoemas.htm] This is an aesthetic inherent to many electronic works, text being replaced by other texts; text is constantly being shown and removed, or put on the plate and devoured so the next course can be served. At the end, in a modernist gesture, the overall visual structure is shown again and a polyvocal soundtrack including the author reciting the lines is heard; there the user can use the mouse to illuminate any of the poem’s lines and bring the reading of that line to the fore.

In the last line to appear in “Sem-saída,” “nunca saí do lugar” [I never moved from this place)], Augusto could be speaking of his engagement with anthropophagy. It is not surprising that it is easy to see these works as concrete poetry extended, as they require “new forms of linguistic codification that imply a stricter involvement between the verbal and the non-verbal” (Greene n. pag.). Augusto’s digital works represent a transparent transition from his theorizing to practicing of this kind of new poetry, spatial poetry, a temporal-spatial idea or conception, which he leaves as a possibility by way of invention. A formidable degree of anthropophagy, used to “in-spire and ex-pire information from the outside to develop and produce new information,” is revealed in these efforts (Email 2006).

Certainly there are other poetic interpretations of anthropophagy, and other sorts of artistic engagement with the concept. Nevertheless, Augusto and other concrete poets approach anthropophagy in distinct and profound ways: (1) through translation/transcreation, “original” writings are processed and re-languaged; (2) through direct incorporation of external elements (including multiple languages, images, and symbols) in the generation of original expression; and (3), in the mechanical presentation of the work (and inventing new technological/navigational structures). While some of these traits are undoubtedly present in his analog poems, it is in recent digital multimedia works that Augusto is best able to represent anthropophagic mechanics, which, as Charles Bernstein writes, give us “a way to deal with that which is external…by eating that which is outside, ingesting it so that it becomes a part of you, it ceases to be external. By digesting, you absorb” (n. pag ).

An evolving, transitory

art, instigated from a moment of possibility, has thus been sprung with

intent, aesthetic polemic, and, plausibly, political depth. In the

world of just globalization artists absorb, through consumption, to

become another. To transform, one must be transformed. To ignore the

world, to have its makings at your fingertips and its attention through

the network, and not incorporate its conditions into a progressive

scheme may not be mandatory. Doing so, however, opens up new

possibilities for the synthesis of discrepant cultures and expressive

histories.

Notes

(1).

Other associated essays from the same period are collected in the

volume The Anthropophagic Utopia. Comment on the

translation of the title of "Manifesto Antropófago": in a recent email,

André Vallias observes that the title “should

be translated, in my opinion, as ‘Anthropophagus Manifesto’.

"Antropófago" is an adjective” (Email 2006).

(2).

Works by at least two other major figures of twentieth century art in

Brazil, Raul Bopp and Flavio de Carvalho, would be at the top of the

list of artists whose works seriously embrace anthropophagy. I would

like to thank both Lucio Agra and Marcus Salgado for bringing relevant

works by historical and contemporary artists to my attention, and for

our ongoing dialogs, which have substantively contributed to my

discussion of the topic.

(3).

References to his work were not common until the publication of the

manifestos of the Concrete poets in the 1960s.

(4). The allusion to Camões is in the fifth poem of the series, “dias…”.

(5).

The Profilogramas series, as well as “Intraduções” (see below in

essay), were both initiated in an earlier collection, Despoesia

(São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 1994).

(6). While confirming that this type of work is transcreation, de Campos writes “I prefer to call this kind of translation ‘tradução-arte’, deriving the term from “futebol-arte” (art-soccer), used to distinguish characteristic ballet-like Brazilian football… (Email Oct 2006).

(7). The Portuguese translation of Bassho´s complete haiku is: “velho lago/mergulha a rã/fragor d´água” (or, Into the ancient pond/A frog jumps/Water’s sound!).

(8). For more discussion of this work and other early videopoems, see my essay “A Vanguard Projected in Motion: Early Kinetic Poetry in Portuguese (Sirena 2005: 2, 152-165).

(9). Digital poetry, as defined by the authors of a 2004 anthology titled P0es1s: Aesthetics of Digital Poetry, “applies to artistic projects that deal with the medial changes in language and language-based communication in computers and digital networks. Digital poetry thus refers to creative, experimental, playful and also critical language art involving programming, multimedia, animation, interactivity, and net communication” (13). The form is further identified as being derived from “installations of interactive media art,” “computer- and net-based art,” and “explicitly from literary traditions” (15-17). “Medial self-referencing” in digital poetry, wrote the authors of p0es1s, “refers to poetic interest in the ‘concrete’ (as defined, for instance, by concrete poetry) ‘material’ of the language itself” (25).

(10).

Incidentally, the CD-ROM was engineered by a pioneering Brazilian

digital poet from a subsequent generation, André Vallias. Vallias, a

graphical designer based in

Works Cited

Oswald de Andrade, "Manifesto Antropófago," Do Pau-Brasil à Antropofagia e às Utopias: Manifestos, Teses de Concursos e Ensaios, introd. Benedito Nunes, 2nd ed., Obras Completas 6 (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1972), p. 18; the same is translated by Alfred Mac Adam as "Anthropophagist Manifesto" in Latin American Literature and the Arts 51 (Fall 1995), 65-68. See http://www.agencetopo.qc.ca/carnages/manifeste.html for an online translation by Adriano Pedrosa and Veronica Cordeiro.

---. O

perfeito cozinheiro das

Bailey,

Richard W., ed. Computer Poems.

Bernstein, Charles. “De Campos Thou Art Translated (Knot).” Online. http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/bernstein/essays/de-campos.html.

Bishop, Elizabeth, ed. An Anthology

of Twentieth-Century Brazilian Poetry.

Block,

Friedrich W., Christiane

Heibach, and Karin Wenz, eds. p0es1s: The Aesthetics

of Digital Poetry.

---. Email to Chris Funkhouser, November 2006.

---. Não

Poemas.

---. Personal

Interview, conducted by Christopher

Funkhouser and Lucio Agra,

---. Viva

Vaia.

Greene, Roland. “From Dante to the Post-Concrete: An Interview With Augusto de Campos.” The Harvard Library Bulletin 3.2 (Summer 1992). Online. http://www.ubu.com/papers/decampos.html

McCauley, Carole

Spearin. Computers

and Creativity.

Nunes, Rodrigo. “We Have Never Been

Catechised.” Online. http://www.metamute.org/en/we-have-never-been-catechised

Perloff, Marjorie. Radical Artifice:

Writing Poetry In the Age of Media.

Plaza, Julio, and

Monica Tavares. Processos Criativos com os Meios

Eletrônicos:

Poéticas Digitais. Trans. Jorge

Luiz Antonio and Christopher Funkhouser. São Paulo: FAEP-Unicamp

Editora Hucitec, 1998.

Rocha, João Cezar de Castro. Anthropophagy. Online. http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v08/rocha.html

Schütze, Bernard

Andreas. “

Vallias, André. Email to Chris Funkhouser. October 2006.

Veloso, Caetano. Tropical Truth: A

Story of Music & Revolution in