Burning

Down the Canon:

Queer

Family and Queer Text in Flaming Iguanas ) (1)

Sara

Cooper

California State University, Chico

What

do sex, family, comedy, road trips, and latinidad

have in common? The answer of course is the Puerto Rican Diasporic

author Erika

Lopez, who with her innovative series of graphic novels (Lap

Dancing for Mommy, Flaming

Iguanas, and They Call Me Mad Dog)

has established herself as a writer who bravely goes where as of yet

few

authors dare to tread. Her transgressions only begin with the addition

of

graphics to her textual production, going on to flout rules of

structure,

content, and political correctness. (2) Although not a comic book style graphic

novel in the style of Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No

Towers (2004) or Allison Bechdel’s new Fun Home (2006),

Flaming Iguanas: An Illustrated All-Girl Road Novel Thing

(1997)

does reflect the elements of subversion and rebellious confrontation

that may

be found in some of the best women’s (and men’s) comics.(3)

Nevertheless, this study is not an in-depth look at the work as graphic

novel

(the novel’s imbrication of text, line drawings and stamp art being a

departure from that genre), but rather mentions this aspect of

structure as one

more indication of how the author intentionally transgresses literary

and

social boundaries–especially those around gender and sexuality. Indeed

the main character and narrator Tomato Rodríguez–a woman on a

cross-country trek and a quest for identity–questions and ultimately

frustrates every possible gender role expectation, as do many of the

other

characters that she gathers around her. Partially because of the

novel’s

mixed genre and partly due to other insubordinate elements, Flaming

Iguanas shares to a great degree

the mixed blessing of marginalization that women’s comics have enjoyed

(or suffered). This is one of the issues I would like to consider

briefly

here–the novel’s place at the periphery of the United States

literary canon. How and why would this novel be perceived to belong at

the edge

of a literary tradition, rather than central to a new generation’s

production? Still, the edge is indeed connected to the whole, and the

periphery

can’t help but influence the center in some way. That said, what are

the

possible ramifications of the novel’s existence on the fringes of U.S.

mainstream literature? I will argue that in addition to the readily

apparent

visual and verbal edginess, it is also the author’s treatment of family

as an intrinsically queer institution, and her creation of an

inimitably queered

family that ultimately relegate her work to the margins of academic

viability. Moreover,

this apparent weakness, this seeming lack of power or position may in

fact be a

paradoxical source of strength and agency that infuse the novel with a

border-busting queer authority.

The Canon:

Begging to Be Burned

Let us

begin our own

critical road trip with a consideration of the way that the literary

canon

works. This does seem to be the first stop on our journey, and it is a

reality

that cannot help but inform the writing (and reception) of even the

most

iconoclastic author. The canon exists on multiple levels and consists

of an

immensely complex system of selectivity and prejudice that manifests in

not

only whether we read certain works, but also how we read them. A text

can be

marginalized through its complete non-inclusion, through its relegation

to some

allegedly inferior or less viable genre, or through a reading that

ignores

fundamental aspects of the text that would otherwise place it within a

particular

part of the canon. Tey Diana Rebolledo has written extensively on the

ways in

which the canon has ignored entirely or failed to concede complete

legitimacy

to the writings of Latina women. Only in the last decades of the

twentieth

century do we see Latinas being published by specialized (much less

mainstream)

presses, or even included in anthologies of American or Latin American

literature (2005, 13-39 and 56-73). So is it that recently women

writers have

claimed their rightful place as celebrated contributors to a vibrant

American

literature (although to this day women of color often only will be

discussed as

part of the U.S. Ethnic canon). During this same period, when critics

and

professors of literature began to focus on an increasing diversity of

texts

that highlight race, gender, class, and sexuality, there seemed to

remain a few

sticking points that continued to limit the scope of class reading

lists, exam

preparation materials, and academic discussion in general. There is yet

to this

day a literary discourse that is dangerously on edge--a discourse that

pushes

the limits of tolerance and propriety. We are embarrassed and irritated

like

when we hear fingernails on a chalkboard and try to block out or

marginalize

the offending words. After all, as established practitioners of a

venerated

profession, that is, the judgment and interpretation of written works

of art,

why should we pay any attention to the irreverence of disrespectful

upstarts?

As Julia Alvarez wryly comments in Border-Line

Personalities, when someone in one of her family gatherings would

ask

“Qué dice la juventud?” the younger generation:

knew instinctively that the older folks

didn’t really want to hear what we had to say. In fact, every one of us

would have been grounded until the day we were married if we had fessed

up to

what we were doing with and discovering about our bodies. Los viejos

just

wanted to hear the old verities recited back to them…Old and young had

to

hunker together as a familia and comunidad, especially after we arrived

in

crazy gringolandia. (2004, xv)

So the juventud, the youth, the rebels and

anyone who thought differently would keep quiet. Maybe

someone would snort or giggle,

which would earn her a glare and a sharp reminder that she was to be

seen and

not to be heard. After all, the family hierarchs, just like the

recognized

literary historians and critics, have a fairly tight rein on the hoi

polloi.

But when a rebel voice finds a place to emerge, then how do we

respond—by

looking the other way, by remaining complicit in its marginalization,

or by

finding a way to listen through the discomfort? Do the canonical

guardians feel

guilty when pouring salt on what they consider to be slippery and

slimy? Do

they hear our screams? In a way, this is a paper about the paradoxical

coexistence of embarrassing noise and shamed silence.

One example

of this

raucous hush is Erika Lopez's Flaming

Iguanas, a novel that teeters on

a queer edge. The storyline,

characters, and graphics often jar the reader emotionally, sometimes

blatantly

and other times requiring first that the reader traverse the chasm

separating

signifier and signified. For instance, a mixed graphic and text image

of a bag

of salt and a slug appears just after Tomato has fallen yet again on

her

motorcycle. As she picks herself up and starts to ride again, she notes

a frog

in the road and muses over how many of them she has not noticed and

therefore

hit, wondering “how many more critters I was tied to karmically

[sic]” (197). The graphic points to the purposeful killing of animals,

the guilt and shame connected to even the killing of slugs, who share

with

humans at least the capability of producing a sound like a scream as

they

sizzle, melt, and die. The realistic rendering of the slug juxtaposed

against a

stylized and comparatively tiny bag of table salt privileges the

suffering of

the much-maligned mollusk, while subtly jabbing at the human tendency

to savor

another of the gastropods as a delicacy (escargot) when we are not

getting their

cousins out of our garden.

Burn, Baby,

Burn

The

inserted line

drawing, stamp art, and scrawled cursive and print of each page of the

novel

only look primitive at first glance, in reality being another element

that

hints at the protagonist’s constant soul-searching on her journey of

self-discovery. The queerness resides partially in the visual fusion,

partially

in the protagonist’s willingness to speak of a silenced subject, and

partially in the gap of meaning requiring the reader’s complicity. Eve

Kosofsky Sedgwick defines queer as "the open mesh of possibilities,

gaps,

overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning

when the

constituent elements of anyone's gender, of anyone's sexuality aren't

made (or

can't be made) to signify monolithically" (8). While a diligent critic

could find ways to frame the slug graphic in terms of female sexuality

(the

moisture, the wetly curved lines, the abject status of the object),

actually

that is not a requirement of a queer reading. On the contrary, queer

theory

doesn’t fix its squinted eye merely on the sexual, but also involves

questions of race, class, religion, able-bodiedness, and various other

elements

that frame one’s closeness to or distance from normativity. One of the

foundational theorists of Queer Studies, Michael Warner defines queer

as

straying from the normal rather than simply opposed to heterosexual

(xxvi).

Critics such as David Eng and Yvonne Yarbro Bejarano push the limits of

queer

to include issues of race, class, religion, and ethnicity as well as

sexuality.

Bejarano’s oeuvre brings into the fray a complex discussion of the

intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, especially as relates to

cultural

production by women of color (4). In sum, a

queer text may be seen as

subverting any number of standards or traditions, and for Flaming

Iguanas, a graphic such as this is only the beginning. The

graphics and narrative consistently will mark the novel as renegade,

like an

“all-girl” roughneck crew blazing across a literary frontier.

While queer

studies does

encompass the uncovering and twisting of canonical texts and authors,

oftentimes queer criticism will focus on marginalized writers such as

Sara Levi

Calderón, or lesser-known texts by noted authors, like Luis

Rafael

Sánchez' "¡Jum!”

Frequently, queer scholars gently stretch the strictures of

literary

analysis so that it slides into the contemplation of culture, as in

Yvonne

Yarbro-Bejarano's work on Cherríe Moraga (2001). By the same

token,

queer studies can include scrutiny of texts that are radically outside

of the

scope of literary mainstream, to say the least, such as

Yarbro-Bejarano's work

on the newest Latina graphic artists (1995), José Muñoz's

studies

of the trash film star Divine or the Puerto Rican/Cuban performance

artist

Marga Gomez (1999), and Melissa Solomon’s comparison of Erika Lopez and

intellectual diva Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (2002). Whereas these studies

are

undeniable contributions to the study of literature and culture, and do

provide

a possible bridge from the text to new readership, the scope of their

influence

is still relatively small. The mainstream canon remains elusive for

many sorts

of queered cultural texts, and one might ask why such a disjunction

between one

critic's judgment and another's still prevails. Perhaps this gap is due

to the

incredible sense of discomfort that may be generated by the intensive

reading

of a truly queer text; if so many innovative yet somehow compliant

works are

available for study, then why should we knowingly subject ourselves to

the

sense of crawling out of our skin in response to an aggressively odd

and often

offensive creation?

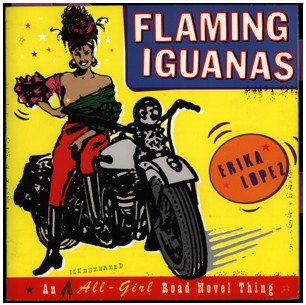

Even

at first glance, and then increasingly upon further scrutiny, Flaming Iguanas is an earthy, eccentric,

and of course queer text -- linguistically, stylistically,

thematically,

philosophically, and sexually. It exists in the gaps and dissonances

that are

celebrated within queer theory, as it crosses borders in every sense of

the

word. Nevertheless, that a text be

considered tolerable in the permissive, rebellious, and even raunchy

milieu of

queer studies is not necessarily equated with acceptability in any

other

traditional field. Flaming Iguanas is

not an obliging text and does not embody a sense of the normal, which

of course

makes it an ideal example of the queer according to Warner and a

perfect target

for ostracizing by practitioners of the normative. It is purposely a

difficult,

and sometimes even exclusionary text, but often in a much different way

than

the body of works written for an intellectual elite, such as the

deliberately

obscure (and of course fascinating) essays by Derrida or Cixous. Only

the

highly and eclectically educated will catch some of the allusions and

references in Flaming Iguanas, but

other elements of the novel are purposefully blatant, vulgar, and crass

Solomon

says “lewd” and “prurient”, 201), such as the front

cover of the paperback edition of the novel.

There are

numerous reasons

that any “serious-minded” scholar of American or U.S. Ethnic

literature might shy away from Flaming

Iguanas. First of all, the novel is published by Scribner Paperback

Fiction

(Simon & Schuster) and is far from being re-released as a critical

edition

with notes and introduction by a properly academic editorial house (not

to say

that just that contingency will never materialize, given increasing

interest in

Lopez’s work). As an aside, one might speculate as to why a major

publisher would give voice to and extensive dissemination of this kind

of

cutting-edge, genre-busting work, when the theoretically freer academy

remains

reluctant to do so. Perhaps the simple answer is that it sells! That,

then, is

another element that must be taken into consideration, that Erika Lopez

is not

the sort of writer who insists on subsisting precariously in a garret

in order

to produce what is purposefully inaccessible to the general reader.

Whereas she

is single-mindedly devoted to portraying what she wants in exactly her

own chosen

manner, she is delighted (as would be many struggling artists) to be

given this

opportunity to bring her work to the public. Interestingly, we have

come to a

point in time at which intelligence and profundity need not be

considered

anathema to sex and humor; I say need not,

despite the fact that the contrary belief still holds sway in some

hallowed

academic grounds.

Other

elements that may

prejudice the more conservative scholar include the back flap of the

paperback

edition, which privileges reviews by queer and suspect publications

such as The Village Voice, the San

Francisco Chronicle, Feminist Bookstore News, and Lambda Book Report, the last of which

proclaims, "There's a sizable, rebelliously tasteless portion of our

reading public who will soon want to make Lopez their cartoonist pillow

queen.” This correlation between the novel and the comic book genre is

enough to earn it scorn or perhaps amused condescension from some

scholars.

Although critics like Charles Hatfield credibly argue the emergence of

the

graphic novel as a legitimate genre garnering important academic notice

(e.g.

articles in the Chronicle of Higher

Education), even Hatfield must acknowledge that for many “the form

is

at its best an underground art, teasing and outraging bourgeois society

from a

gutter-level position of economic hopelessness and (paradoxically)

unchecked artistic

freedom” (2005, xi-xii). As another example of cunning, ironic and

beautifully rendered social commentary in the form of the graphic

novel,

consider the Hernandez Brothers’ Love

and Rockets, which has a considerable cult following but has not

yet

received the analytical attention it deserves.

The concept

of artistic

license brings us to the physical appearance of the novel, which is

both

licentious (pun intended) and unchecked. The font of the chapter titles

approximates the scratching–alternatively cursive and print–of a

blotting ink pen, while the body of the text looks like the output of a

somewhat damaged and imperfectly aligned typewriter. This does bring to

mind a

section of the canon that won critical attention and acclaim exactly

for its

blatant disregard for normative typescript, regular placement of verse

or prose

on the page, and accepted rules of punctuation and grammar. I refer to, of course, the writers of

the modernist period, like Gertrude Stein or Julio Cortázar

(especially

in Rayuela), and even more specific

movements, like the concrete poets. Why is it, then, that the visually

playful

text in a concrete poem by Jorge Luis Borges or E.E. Cummings has been

accepted

fully as innovative yet canonical, while a further development of such

techniques is spurned in a novel like Flaming

Iguanas?(5) I

wonder if

this could be due to the fact that the author departs from a solely

verbal

exposition: the entire manuscript is littered with line drawings and

stamp art,

whose relation to the text is often difficult to ascertain at first

glance,

although indeed becomes clearer upon close consideration.

Underlying these parallels between

specific graphics and textual context, Laura Laffrado suggests that

“Lopez links the disruption of conventional female self-representation

to

the visual disruption of the conventional appearance of the page”

(408). In

many cases she makes visible and inescapable the perverse, abject, and

hybrid

complexity of female gender and sexuality, which can be an unforgivable

excess.

What's worse, the cover is bright yellow and red, sporting the image of

a

Carmen Miranda motorcycle chick showing the onlooker one of her breasts

(6). Here, surely

Erika Lopez has passed the

line of reasonable moderation and fallen into the outlandish. One asks:

Is this

a comic book by a cartoonist, or can this really be called a novel, in

the same

way that we understand the novel, like Lazarillo

de Tormes, Don Quixote, One Flew Over

the Cuckoo’s Nest,

or even Dharma Bums? As an aside, the

fact that the mixture of graphics and text is held in such low regard

in the

United States can be attributed at least in part to the history of the

comic

strip in this country. During the height of McCarthyism, comics were

blamed for

the perversion of America’s youth; the inappropriate gender models of

comic strips were encouraging homosexual fantasies in boys and

destroying

girls’ aptitude for being good wives and mothers. How ironic is it,

then,

that today works like Flaming Iguanas

again are pushing the limits of gender and sexuality as well as genre?

This brings

us to the

discussion of the novel’s content, which is queer indeed. The title

itself serves as a brief plot summary, and as already mentioned, the

protagonist's name is Tomato, as in juicy hothouse, thin skinned yet

sweetly

acidic, unashamedly meaty, round, and red. The narrative ambles

non-chronologically through Tomato's cross-country motorcycle ride (and

the preparations

beforehand), scattering four-letter words and sexual references at

every

turn. Although the narrator is of a

philosophical bent, she embraces a thoroughly contemporary and coarse

expression of her spiritual and intellectual preoccupations. A few

choice

chapter titles include: “Chapter 3: Ashes to Ashes, Crust to Crust”

(13); “Chapter 28: No, Those Aren't Panties, Those are Prayers”

(179); and “Chapter 31: I'm determined to one day understand and love

anal sex because I'm convinced I must be missing something” (190). The

constant juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane is a trademark

characteristic of Lopez’s writing and points to one of the underlying

preoccupations of the protagonist of this novel. Raised in a very

Catholic

culture, Tomato’s tendency to associate sexuality and religion is not

at

all surprising. What does clash, however, is the language that she

chooses to

express these connections. The well-known concept that our corporeal

being will

return to the ground and disintegrate (ashes to ashes, dust to dust),

leaving

our spirit to travel to the afterlife of heaven, hell, or purgatory, is

here

satirized by the changed ending, “crust to crust.” The crust may

call up the image of pie, but a more likely meaning in this context is

that of

the crusty covering of an injury (the cat Tomato accidentally runs

over) or

some sexually transmitted disease (herpes, scabies, or syphilis). Then,

the

comparison between panties and prayers (not directly tied to any

apparent part

of the plot developed in that chapter) and the focus on anal sex

exemplify the

novel’s embracing of the shocking and the inexplicable. The main

character is truly obsessed and fascinated with all that is improper,

but not

to the exclusion of more standard philosophical inquiry. She asks

herself time

and again about her purpose on earth, the definition of love, and the

nature of

coincidence. However, the more scandalous elements do tend to stand

out. If one

could ignore the pop-art facade, then surely the book's irreverence and

its

brash and unapologetic vulgarity would make difficult its inclusion in

the

canon of mainstream literature.

The Last

Straw: Queering Familia

Nevertheless,

if one

practices the sort of criticism that celebrates the twisted, the

irreverent,

and the otherwise queer, the inevitability of the fact that what passes

through

one person's mind will be patently offensive to some of her peers, then

Flaming Iguanas is a rare find. Lopez's

disregard of limitations and taboos takes many forms, as is suggested

by the preceding.

However, there is one aspect that deserves particular study for its

determined

irregularity: the queer aspect of family. Cooper argues that the myth

of the

predictably large and loving, stable and secure Latin American (and by

extension U.S. Latina/o) family is one that begs to be demystified and

recreated (2004, 2). The truth is that not every familia

is composed of the same sorts of members, nor does it serve

always the same functions, and most of all familia

does not create a predictable environment where all are accepted and

protected.

The critic Ralph Rodríguez is bothered by the naïve “notion

that familia is a safe haven, an

outside to society’s structuring power relations. Understood in this

manner, familia has been the

operating trope for forming Chicana/o social movements, once again

missing the

multiple ways in which family itself can be oppressive and generating a

nostalgia for a family structure that might save us from the wicked

world” (2003, 74). He suggests that the queer subject must go beyond an

innocent and uncritical vision of family, but rather than attempting to

escape

or deny family completely, the queer must queer family. His specific

expression

is to “scratch” family, in other words “embracing and yet

distancing oneself from family” (81), a concept that comes close to

José Muñoz’s theory of disidentification.

Rodríguez

advocates “the creation of new sets of relations and new lines of

personal connections that offer us a language and practice of

possibilities for

constructing family” (76). The queer familia

that this Chicano critic envisions for his specific culture is exactly

what

Erika Lopez paints from her Nuyorican mixed-race subjectivity in Flaming Iguanas.

Over and

over the

narrator uses insolent humor to undermine the vision of mainstream

heterosexual

family as picture-perfect. Tomato wryly comments that her best friend

Shannon

had left her to become a “Stepford wife with edge” and get

“free stuff” through matrimony (36); she recounts how outside of

her apartment a teenage male hooker is let out of a car sporting one of

those

“proud parent of an honor student” bumper stickers (38); and she

admits that she herself has tried to be the ideal trailer trash wife

with Bert,

her “darling little alcoholic” (145). Bert’s family ethic can

be deduced from what passes for a proclamation of affection: “Well, I

didn’t say I’d marry you or anything. Not yet, anyway. But you could

hang out here, and uh. . . we could hang out together, and well if you

wanted

to or if you got pregnant, well we could get married” (145). Matrimony,

then, is a civil institution that is linked to consumer culture, the

production

of progeny, the support of homosexuality and prostitution, and

premarital sex

ending in self-imposed shotgun weddings. On Tomato's motorcycle journey

she

does her part to further subvert the sanctity of the idea of

traditional

marriage and family, having a brief tryst with her two Canadian Johns.(7) Tomato explains:

“These were not

the raping and pillaging kind of Canadian guys. They were family men

who had

desk jobs, lived with lawns, and I was their Stranded Biker Girl

Experience” (125). Again, the appearance of social conformity seems to

be

much more important than any actual compliance with vows of monogamy or

honesty; in this case the physical travel outside of their domestic

sphere

leaves men with the assumption that the regular rules do not apply.

If she is

the Canadian

Johns’ experience, their incursion into the queer, they simply serve to

reinforce for her the unrelentingly flexible parameters of acceptable

family

composition and behavior. Tomato’s nuclear family is doubly

queer–both odd and gay–although they sound somewhat straitlaced and

cranky. She explains that her mom and Violet–her mom's girlfriend of

fifteen years–“split up all the time and move out of each

other’s houses. Between them, there are like four or five houses all

over

South Jersey because some of them are ‘too painful’ to move back

into” (51). One of Tomato’s visits home comically highlights the

couple's obsessive boundary issues and their “processing” based on

decades of therapy, a caricature of stereotypical lesbian love. This

provides

the backdrop for Tomato’s confession to her mom that she has been

contemplating becoming a lesbian herself. As Tomato bears her soul, the

older

woman reads and drinks wine in the Jacuzzi, forgetting to listen to her

daughter’s confession and plea for information. This is when Tomato has

an epiphany about her queer but not-queer family, that actually her

mother and

Violet spend most of their time avoiding the thought of what or who

they

actually are. “Violet was fifty-five years old, Catholic, and in denial

about loving women. My mother just figured it was no one’s business. So

it got to the point where they were pretending they weren’t

‘lesbians’ with each other, especially because they hated the word.

They thought it was harsh to the ear with the ‘z’ crashing right

into the ‘b’ sound” (176). That this episode of the

contradictory evocation and denial of a lesbian sexuality occurs in a

hot tub,

the setting of so many pornographic as well as drunken and denied

seduction

scenes, is an irony not lost on the reader. At the same time, the two

girlfriends bickering and the studied isolation that constructs an

invisible

boundary between mother and daughter deflate the erotic component of

the

lesbian relationship. It is just another white elephant in the Jacuzzi.

Nevertheless,

Tomato’s romanticization of the lesbian connection (and the gay element

of the queer family) is understandable, considering the alternative

modeled by

her father. She remembers that when she and her 7 year old sister Glena

go to

stay with Dad, who drinks too much and beds his coed students, he ends

up

punching his youngest daughter because she didn’t wash her hair (68).

The

family’s exemplar of the patriarchal hetero-normative culture does not

exactly inspire confidence or emulation. At some point Dad has moved to

California and started running a sex-toy shop with a lesbian named

Hodie,

further complicating the oddity of the family mythology. Now, in a

setup worthy

of the soaps, Tomato is taking her motorcycle cross-country to see her

dying

father, but by the time Tomato arrives, her father has already died,

leaving

her at somewhat of a loss. The dearth is soon eliminated as Tomato

focuses her

road-fueled sexual excitement onto the older, experienced butch. Hodie

finally

provides her with the opportunity to try full-scale sex with a woman,

and work

through some childhood issues (the protagonist mentions the Electra

Complex) in

a non-therapeutic atmosphere (250). Nonetheless, this experience

doesn’t

turn out exactly as she anticipates or dreads. Tomato exclaims:

To my relief, the next morning

I didn't

feel like a member of a lesbian gang. I didn't feel this urge to

subscribe to

lesbian magazines, wear flannel shirts, wave DOWN WITH THE PATRIARCHY

signs in

the air, or watch bad lesbian movies to see myself represented. No. I

wanted a

Bisexual Female Ejaculating Quaker role model. And where was she,

dammit?

(251)

Queer

family does not

admit the restraints even of an alternative or subculture, and the

protagonist

does not shy away from claiming her own unique identity, even when that

transgresses the limitations implied by any externally-conceived label.

Quite

the opposite, she is delighted to ignore societal norms, or better, to

taunt

those around her (especially the reader) by going one step further.

Notwithstanding

the

violence, enmeshment, and sexualization of the rest of the family

system,

perhaps the most outlandish relationship of all is that between Tomato

and her

sister. The two are close

emotionally as well as in age, although Tomato has always felt like the

cretin

of the family, without proper manners or an acceptable form of

expression. While

her brash vulgarity permeates the novel, one scene in particular

represents the

pinnacle of transgression of the family ideal:

I sat next to my sister on the sofa and

started blowing in her ear. She smacked me on the leg so she could

watch

TV.

"Don't worry, Glena-Glane.

Momma-girl

knows about our special drive-in-movie kind of love," I said in a cheap

southern accent.

I joke about incest with my

sister and

thank God it doesn't bother my mother.

When I want to know if I look good in something, I ask Glena if

it makes

her want to have sex with me. When she doesn't say anything I like to

believe

it means, "why, of course." I tell her if we were back in West

Virginia we wouldn't have to be ashamed of our love and she could bear

my

children. And in case something went wrong with the kids, there are

special

schools, you know. (53)

The

protagonist's ease and

humor diffuse the absolute seriousness of the incest taboo; at the same

time,

discussing incest so blithely is intrinsically queer. The desire and

contradictory revulsion that surround incest are principal social and

psychological motivators. However, there are many who would use

Tomato’s

running incest joke (and another jest two pages later about bestiality)

as

another reason to condemn her family as singularly odd and

unacceptable. In

this passage, the threat of sexual transgression within the family,

combined

with the skewed representation of the protagonist's gender and related

power to

impregnate is enough to make most readers a bit edgy, to infuse their

laugh

with a nervousness that can permeate the entire reading. Then too,

Tomato’s comments associate this improper behavior with a certain class

and regional area, a linking which underscores other class-related

gender/sexual stereotyping, like her attempts at being a trailer trash

wife. It

would take a determinedly ingenuous reader, however, to view said

scenes as

examples of classist or discriminatory rhetoric. Lopez’s

strength lies in laughing

at herself just as she laughs at the hegemony and the disinherited.

Indeed,

the most compelling and

valuable contribution made by this novel is the disidentificatory

strategy of

recuperating these emotionally loaded issues and performing them with a

humor

that recognizes the patently ridiculous within the abject. Within lies

the freedom

from internal and external discrimination, as explained by José

Esteban

Muñoz. “Let me be clear about one thing,” warns

Muñoz:

disidentification

is about cultural, material,

and psychic survival. It is a response to state and global power

apparatuses

that employ systems of racial, sexual, and national subjugation. These

routinized protocols of subjugation are brutal and painful.

Disidentification

is about managing and negotiating historical trauma and systemic

violence…I have wanted to posit that such processes of

self-actualization

come into discourse as a response to ideologies that discriminate

against,

demean, and attempt to destroy components of subjectivity that do not

conform

or respond to narratives of universalization and normalization. (1999, 161)

Lopez

embraces even the most

painful elements of her experience, but never in an innocent manner,

rather as

a prelude to a process of transformation that shifts the locus of power

into

her own hands. If she has lived out her idealized version of Anglo

working

class life, perhaps initially believing that she was doing so to escape

her own

ethnic heritage and the inescapably connected social disapproval, then

she also

has experienced an epiphany of sorts around race and class. After her

time with

Bert, she understands the nonsensical nature of a social hierarchy that

can

value spam above beans and rice, or vice-versa. Moving from the barrio

to the

trailer park essentially makes no difference in her life, as long as

she is

still attempting to shift responsibility away from herself for her own

identity

and future. Bert’s whiteness cannot negate her brownness, his

gender-normativity cannot relieve her of her queerness, and his

oblivious

stupidity cannot take the edge off of her critical acumen. However, he

can

provide a mirror that eventually reflects the reality of her situation:

she is

a mixture of artist and working class, United States Imperial Anglo and

colonial Puerto Rican, gay and straight, passive and assertive. In

order to

gain a sense of who she is, she must identify with the disparate

elements of

her makeup and then morph them into her own construction of self.

Tomato’s

hybrid

identity, one that shies away from full identification with any one

group, be

it ethnic, social, or sexual, brings up another issue related to the

transparent borders that circumscribe any particular field. Some queer

readers

can thrill in the tension that arises from the perverse, in this case

the

complete disregard of censorship around family and sex. On the other

hand, it

is important to note that Tomato's somewhat unflattering portrayal of

her

lesbian mother and her insistent queering of family and individual

sexuality

mean that Flaming Iguanas is not even

particularly attractive to all sectors of gay/lesbian studies (8). Her

unapologetic bisexuality can be seen as betrayal, sell-out, and

insulting, and

as an expression of the younger generation runs the risk of undermining

the

tenuous popularity (or in some sectors of culture and the profession

tolerance)

of the gay lifestyle. You can almost hear the reaction of

serious-minded

lesbian feminist separatists: "Tomato and the author are both young

upstarts, without two morals to rub together, and a serious identity

crisis to

top it all off." In discussing her non-monolithic portrayal of

sexuality

in the novel, and her general lack of self-censorship, Erika Lopez

acknowledges

that some lesbians and gay men have criticized and/or ostracized her as

a

direct result of this novel. Along these same lines, claiming that 90 %

of the

novel is autobiographical, Lopez admits to having angered a lot wider

range of

people than that, not the least of whom are the wives of the married

Canadian

men --the aforementioned family Johns (class visit). If the author will

not be

held back by the fear that her family and friends, even her immediate

queer

community will react poorly to her counter hegemonic narrative, then

certainly

she is not going to back down at the threat of non-inclusion in the

mainstream

canon.

I suggested

above that

there are more ways than one to relegate a literary work to

invisibility within

academia. The queering of Flaming Iguanas,

or in other words, the fairly effortless work of highlighting the queer

in this

novel, makes clear many of the reasons why it is not an easy addition

to the

canon. The physical appearance of the book, the bawdy tone, the use of

a young

and patently offensive language, the foregrounding of a sexually

transgressive

ethic, and the very queer representation of family make it

controversial, even

dangerous.(9) The novel exists on a queer edge,

and as such is not

easily embraceable from the center, as represented by the canon of U.S.

American

(Ethnic) literature. Yet, perhaps there are reasons why this is an

unfair

evaluation and treatment of the novel.

There is an

aspect of

Lopez and Flaming Iguanas that

insinuates, "Don't take me seriously, don't take this

seriously, and don't make the mistake of thinking that I

do." Flaming Iguanas is

self-consciously performative, as is the author when she reads from or

talks

about the book. Her gestures are bigger than life, and somewhat in the

mode of

a boisterous, sexy, long/frizzy-haired Carlos Fuentes, many of the

lines are

pronouncements (class visit). Unlike those of the Mexican canonical

author,

Lopez's revelations are aggressively tongue-in-cheek, funny, and sexual

in

nature. This tendency to pronounce and opine is one of the many

characteristics

that the author seems to have bestowed upon her main character Tomato.

A case

in point is a scene in which the protagonist is watching some lesbian

porn: "I

hung up the phone, lit a cigarette and watched the video as one of the

high-haired girls sucked wildly on her aerobic instructor's nipples

without

smearing her lip gloss, and I asked my cat, 'Hey Nena, come over here.

Do you

ever fantasize about something and then after you get off, think, oh, that is so stupid?' She looked at

me, and her eyes said all the fucking

time" (178). Although the protagonist's packaging of her nuggets of

wisdom suggests a generation-X posturing, it may be just this fresh

framing

that will make the age-old message intelligible and relevant to readers

of the

new millennium.

The

question of whether

to include Flaming Iguanas in the

lists of recommended readings for scholars of American (and

specifically

Latina) literature brings to mind the question of separation of high

art from

low art, now a subject of debate for some decades. This novel crosses

genre

boundaries, incorporating the popular and vulgar along with the poetic,

and

looses the voice of a renegade woman onto the sensitivities of a

literary

elite. Paul Julian Smith and Emilie L. Bergmann caution us that "the

question of drawing the line between the native and foreign, proper and

alien,

is always a complex one" (1995, 2). Yes, Erika Lopez may seem foreign

and

alien when viewed alongside of more mainstream continental Puerto Rican

authors

like Esmeralda Santiago. However, critics like Goldman assert that the

value of

the novel is exactly its “narrative that weaves together the

conventional

and the radical… construct[ing] a queer Latina romance that is both

legible and desirable” (13). Moreover, the work has its place within

literary history: only think of the picaresque, the road novel, and the

novel

of epiphany. Lopez consciously includes direct literary allusions to

evoking

these classic traditions, with mentions of Kerouac, Hunter Thompson,

Henry

Miller, and Erika Jong (27). With respect to this point, Goldman’s

study

cogently explicates how the specifically Latina consciousness “is

reconfiguring

traditional inscriptions of sexual tourism. In [the] novel, the

national

landscape becomes the space of sexual tourism, and the transcultural

and

transgressive are interwoven in a single trajectory that both produces

unexpected results and rewrites the conventional juxtaposition of

difference

and displacement” (4).

Is she or

isn’t she? Only her hairdresser knows for

sure…

If Flaming Iguanas is Literature (with a capital L),

deserving of

critical merit and inclusion in the wide range of privileges of that

classification, can we go further to posit that it forms a legitimate

part of a

specific canon, such as that of the Puerto Rican Diaspora? Are there

elements

that mark the work as belonging, beyond any shadow of a doubt (because

we do

have to admit that the jury here will assume the guilt, the lack, or

the

legitimate invisibility of the work until proven wrong)? In general,

the queer

Hispanic text has included historically (in the short visible history

that

exists) a sharp and slippery questioning of subject positions and

identities,

including that of ethnicity and national identity (Bergmann and Smith

1995, 2).

Specific issues that have been seen as key in the analysis of other,

canonized

works of Puerto Rican Diaspora literature include immigrant and

bicultural

identity, the complications of language, questions of color and other

physical

markings of race. One of the foremost scholars that interpolate

questions of

anti-normativity within those of Puerto Rican identity, Lawrence La

Fountain-Stokes suggests that Erika Lopez’s work is distinctively

Boricua, but that her brand of “Puerto Ricanness assume[s] a

significantly different spin” (294).

As might be

predicted,

Lopez's treatment of Latinidad and Puertorriqueñismo

is as queer,

irreverent, and edgy as the rest of the novel, but it is undeniably

there. As

such she shares a liminal yet important space with queer Latinas such

as

writers Achy Obejas, performers Carmelita Tropicana and Monica

Palacios, and

critics like Michelle Habel-Pallán. She may be writing from an

imposed

closet, but she definitely is situated within the Latino Diaspora

solar, to

adapt Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s conceptualization of Chicana/o pop

culture

texts as a place where the conjunction of ethnicity and sexuality is

most strongly

articulated (2003, xxi-xxiii). In the first pages of the novel, Tomato

mentions

her "huge Latin American breasts" (2), and her code switching

includes such gems as nicknaming a lover "Hooter-mujer" (248). Laffrado

explores in some detail the way in which the line drawings and modified

rubber

stamps in this and other Lopez novels “refigure” and

“ironize” societal images of the Latina. “These

overdetermined figures mock the social framing of Latina women… Lopez

reworks these stereotypes to give them female agency, self-possession,

and

sexuality” (411). Equally interesting are the ways in which Lopez

approaches the protagonist’s contemplation of her own mestiza Boricua

identity. In one monologue she explains:

I don't feel white, gay,

bisexual, black, or like

a brokenhearted Puerto Rican in West Side Story, but sometimes I feel

like all

of them. Sometimes I feel so white

I want to speak in twang and belong to the KKK, experience the

brotherhood and

simplicity of opinions. . . Sometimes I want to be so black, my hair in

skinny

long braids, that black guys nod and say 'hey, sister' when they pass

me by in

the street. / I want the story, the rhythm, the myths that come with

the color.

. Other times I wish I was born speaking Spanish so that I could

sound like I

look without curly-hair apologies.

(28-29)

What is in

focus here is

not only the impossibility of either embracing or denying all facets of

an

immigrant and hybrid identity, but also the slippage between craving

and

repulsion. The protagonist wants a purity of experience that allows an

almost

mystical exultation in each part of her, yet must disavow and denigrate

her

complete self. One is reminded of the seductiveness of the abject and

the

compelling force of desire (sexual and philosophical hunger) that

drives both

the creation and the reception of the queer text (10).

However,

the most

telling remarks that mark Flaming Iguanas

as a novel of the Puerto Rican Diaspora hark back to the central

disturbance of

this paper, that of the queer family. One must recognize that this is

not a

comfortable commodification of Latina identity, or of Puerto Rican

culture,

packaged to sell a certain limited and predetermined image of latinidad lite, a tendency lamented by

Juan Flores. The protagonist describes her own sense of queerness in

the midst

of her family, her Puerto Rican hybrid family that embodies her past

and

present as much as it eludes a direct correspondence with her own

perception of

self. Just as the family doesn't conform to a traditional picture of

heterosexuality,

homogeneity, or domestic bliss, there is no more conformity of outward

appearance than of style. Tomato's mother is light-skinned and her

father dark,

leaving the girls with mixed characteristics as well. The protagonist

explains,

"My sister ended up with pretty yellow Perdue-chicken skin, and when

she

gets a tan, she's golden, and I call her my little pollo.

. Me, I ended up kind of gray brown" (54). However,

some features like Tomato's pointy nose and curly hair leave others

wondering

how to categorize her, just as she is confused herself. In fact, she

shares the

racial mixture and social confusion characteristic of Caribbean

islanders who

immigrate to the United States, where black and white is not just a

fallacy,

but is a dividing line that does not admit any grey area. Clearly, the

institution of family is where the concepts of racial difference

continue to be

perpetuated, as children are differentiated by their good and bad hair,

their

“tan.”

As the

novel winds down,

it becomes clear that the protagonist has not had the sort of complete

catharsis that she had hungered for--she has not found a concrete and

unchallengeable identity, sexually or any other way, still not being "a

real Puerto Rican in the Bronx. . . a good one-night-stand lesbian. . .

[or] a

real biker chick" (241). As Melissa Solomon argues, Lopez might be best

classified as a “lesbian bardo,” in that she portrays and explores

“the transitional spaces between different and conflicting definitions

of

lesbian” (203). Looking at the final words of the novel, one wonders

whether Lopez may invoke an odd, twisted, and queer note of hope that

offers an

escape from the false dichotomy of hetero-homo. Ever the artist and the

idealist, Tomato envisions working with her father's ex-partner (for

the moment

her lover) to create a line of fake penis postage stamps, which would

be

successful because they "are all about penetration, communication, and

dreams coming true in front of a warped circus mirror for EVERYBODY"

(257).(11) In a

way Tomato

is suggesting that she take on the strategies of the patriarchal and

hegemonic

in order to perpetuate her own counter hegemonic, non-normative

artistic

vision. Her vision, however, is inclusive in the extreme: she wants

“EVERYBODY” to benefit from the “warped circus mirror.”

Like in the circus sideshow, where indeed no one can escape from the

strangely

transformed image of self that appears larger than life, no one is

exempt from

personal identification with this novel, symbolized by her postage

stamp

project. In the two-page representation of penis stamps, Lopez/Tomato

have

included such a diversity of imagery that every reader is sure to

recognize

many and find some personal connection with at least a few. Some penises are historical, like the Ye

Olde Plymouth Rock Penis, the Penis Posse, and the St. Valentine’s Day

Penis Massacre. A few will spark recognition only in those with some

level of

art history knowledge, like Penis Descending a Staircase and Andy

Warhol Penis.

In contrast are the contemporary figures and borrowings of popular

culture:

Fabio, Prince Charles, Kate Moss, the X-Files, and Absolute Vodka.

Others

humorously bring to mind very general experiences, like the Gas Station

Penis

Map, the Sunburn Penis, or the Penis Using a Litterbox. Some

confrontationally

juxtapose the penis with childhood images such as Bozo the Clown and A Christmas Carol (the Ghost of Penis

Present). Even more provoking, perhaps, are the various religious

scenes like

the Zen Penis, the Buddhist Penis, and the Penis Last Supper. It seems

as if

Lopez (and her protagonist Tomato) want to be sure to thumb her nose at

every

sacred icon and tradition—an equal-opportunity smorgasbord of irony and

social criticism. She screams that the penis is ubiquitous (which it

is), and

it does not belong uniquely to the patriarchy. Rather, here the image

of the

penis as central element of everything recalls Tomato’s

conceptualization

of queer family throughout the novel. We are all, at heart (or at

penis), kith

and kin, and we are all inescapably odd, hybrid mixtures of the

acceptable and

unacceptable.

From Puerto

Rico to New

Jersey to California is a winding road, of asphalt, words, and skewed

visions. Has

Erika Lopez, like a conflated Latina version of Thelma and Louise,

taken a

family road trip of self-discovery, only to shoot right over the big

wide edge?(12) Will

she shoot off the edge of

propriety, sobriety, and literary piety, which instead of notoriety

will gain her

only a whisper or a whimper? Has her queering of family and literary

form

inescapably marginalized her and disincluded her from the canon? And if

it has,

is this a good or a bad thing? If the canon is by definition

normalizing, then

perhaps Flaming Iguanas can only

retain its transformative and critical function on the edge, where

canonization

cannot disempower its discourse. From this vantage point Lopez can

continue to

make obscenely loud noises in the forest with "no one" official

around to "hear." Perhaps both the longstanding expectations and even

the passing fancies that inform literary criticism, and thus to some

extent

what passes into the canon, would only be a hindrance to a work like Flaming Iguanas. On the one hand, its

incursion into the comic or graphic novel genre is in essence a

thumbing of the

nose at rules and regulations. As a highly creative and underground

genus,

comics (like queer literature) are in some ways anathema to the very

ideals of

a literary canon. Hatfield warns that “it makes no sense, and indeed

would be bitterly ironic, to erect a comics ‘canon,’ an

authoritative consensus that would reproduce, within the comics field,

the same

operations of exclusion and domination that have for so long been

brought to

bear against the field as a whole” (2005, xiii). On the other hand,

Erika

Lopez’s novelistic production as a whole does fit into another category

of cultural production that also has defied convention and survived

attempts at

silencing it, that of U.S. Latina writers, graphic artists, and

performers.

Returning

to previous

thoughts on silence and admissible conversation, we can celebrate along

with

Julia Alvarez that a new generation of Latina writers is consistently

and

coherently challenging the long-time restrictions of what may be said,

or to

extrapolate, what may be written.

These wise, funny, very smart,

and

passionate young women are speaking up. In fact, if I were to single

out the

single most important change in this new generation, is that these

mujeres are talking,

and how. They’re confiando and fessing up, and that feels like the

strongest bond, what creates a true community, one that doesn’t leave

out

the thorny question or answer we don’t want to think about. (2004, xvi)

This, then,

is the

advantage to existing on the fringe of the traditional literary canon

at this

particular point in time: the fringe is growing at an incredible rate

and

gaining strength in the energy and tension inherent in its push-pull

relationship with mainstream culture and literature.

An alternative canon that embraces U.S.

Latina queer writers has come into a position of power that insures

continued

existence despite opposition and may even be able to disregard the

foundational

assumption that a cultural elite has the right to judge the value of a

new

novel or even a new genre. In this young forest, the trees can fall and

be

heard notwithstanding the most obdurate deafness engendered by

entrenched tradition

and hetero-normativity. What’s more, the existence of this counter

canon actively

encourages a frank and loud engagement with formerly silenced topics.

Erika

Lopez thus joins the ranks of outspoken Latinas like Alicia Gaspar de

Alba,

Cherríe Moraga, Nina Marie Martínez, and the novísimas

represented in Robyn Moreno and Michelle

Herrera-Mulligan’s Border-Line

Personalities (2004).

The mixture

of verbal

and visual elements in Flaming Iguanas

bring it closer in essence to the Chicana and Latina performative

pieces

studied by Michelle Habell-Pallán in Loca

Motion. Habell-Pallán explains that the artists she studies

are

“important because they construct transnational imaginaries within the

Americas that are shaped by a particular historical moment, politics,

and

humor” (2005, 2). Moreover, like Erika Lopez, they bring in questions

of gender

and sexuality alongside of race, nationality and ethnicity. Finally,

they are

shaped by the emergence of a powerful pop-culture, punk/hip-hop

aesthetic that

directly challenges the “neoconservative queer bashing and

anti-immigrant

hostility” present at the end of the twentieth century (2). If indeed

Lopez falls into the general terrain of the artists studied by

Habell-Pallán, then probably the critic’s most helpful and

illuminating insight that we may transfer to this discussion of Lopez

is her

understanding of the underlying tone and ideology of the works in

question. In

Habell-Pallán’s words, “Although acknowledging that their

point of origin is important, these artists are much more focused on a

politics

of destination” (4). What’s more, “their engagement with pop

culture is subversive to the degree that it has hope for an America

that has

yet to live up to its democratic possibility” (6). I think that Flaming Iguanas is Erika Lopez’s

manifesto of hope for herself, her family, and her Latina identity. In

the

novel Tomato has found a way to gather to herself the strength, ethnic

pride,

and history of traditional family without giving up a single iota of

the

quirkiness, sensuality, and rebeldía

of her own non-normative soul. Yes, the influence of her Puerto Rican

heritage

and Nuyorican youth is a beloved part of her identity, as are all of

the gender

role expectations that stem from both, but this is merely her origin.

More

importantly, this All-Girl Road Novel

Thing never ceases to emphasize movement, transition, change.

Reflecting a

centuries-old belief of this country, she shows that identity and

destiny can

only be found in pushing forward the frontiers. However, despite the

fact that

she literally follows in the footsteps of her ancestors in crossing the

continent, the true frontier Tomato is forging is in her perspective on

life

and family. The queer family, as well as the queer text that

transgresses

boundaries meant to keep literature in line, is in truth a reflection

(albeit

in that circus mirror) of the only reality that we have. It will be in

the

loving acceptance of a queered reality, an embrace in which the warm

pressure

of our own bodies changes the shape of the embraced every time, that we

have a

future.

Endnotes

(1). I would like to gratefully

acknowledge

the substantial commentary of Naomi Lindstrom, Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano,

and my

many esteemed colleagues in Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social,

all of

which inspired me to expand, revise and update the original paper

presented at

the Modern Language Association’s Annual Convention in 2000

(Washington,

D.C.). The conversation generated at that panel, “The Invisible Canon:

Forgotten Names, Marginalized Texts,” also provided much-needed

stimulus

and provocative questions. Thanks as well to Dara Goldman, who was

generous

enough to send me a copy of her paper given at the 2006 LASA conference

in

Puerto Rico.

(2). Given the similarities between

Lopez’s work and feminist graphic novels, her subversive power should

be

of no surprise. According to critic and historian Sherrie A. Inness

“comic books are also at the cutting edge of exploring new definitions

of

gender because of their marginalization, which allows them to be what

Ronald

Schmitt [in Deconstructive Comics] identifies as an ‘important

deconstructive and revolutionary medium in the 20th

Century’” (153). Inness

goes on, explaining that “this deconstructive power is one of the

reasons

feminist theorists should be interested in comic books—texts that can

create alternative worlds in which gender operates very differently

than it

does in our own real world” (141).

(3).

More visually related to the mainstream comic strip, Spiegelmen’s Maus, Maus II, and especially In the Shadow

of No Towers have been

garnering serious critical attention.

See, for example, Marianne Hirch’s Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and

Postmemory (1997) and

the October

2004 issue of PMLA that features

images from The Shadow on the front cover as well as discussion of the

work

itself and the genre in Hirsch’s editorial.

(4).

See, for example, “The Lesbian Body in Latina Cultural Production”

and The Wounded Heart: Writing on

Cherríe Moraga.

(5).

Although of course it is much too soon to tell if indeed Flaming

Iguanas will be accepted into any particular category of

the canon, originally I was inspired to write on the

“unacceptability” of the novel due to my experience in a Queer

Theory reading group at California State University, Chico in 2000. A group of staunch feminists with

interest in the burgeoning field of queer studies, we read both

literary and

critical texts over the course of a semester. When

we read Flaming Iguanas, despite the novel’s strong

woman protagonist

and sex-positive message, notwithstanding the innovative stylistic and

structural elements, all of the group members but myself and one other

decided

that not only did they not like the novel, but they were sure it wasn’t

real literature. It was too pop

culture, too course, and too flippant. It was a comic book, one said.

It did

not make a stand politically or socially, another complained. It undermined the progress made by gay

and lesbian activists over the past three decades.

Perhaps also they found troublesome the

fact that, as critic Laura Laffrado points out, “The model of female

subjectivity inscribed and visualized in Lopez’s texts is compulsorily

‘I’-centered; it does not promote a conventional notion of

belonging to a female community as a basis of self-representation”

(408). I found it significant that the

only

other woman who shared my opinion was quite young, of the same

generation as

the author. Although I readily acknowledge the limited scope of this

one

personal experience, I have noticed that the critical scholarship on

Lopez’s work does tend to come from the newer generations of scholars

(those of us in our 50’s and younger). The novel also has been a

resounding success in the classroom, which suggests that a future

generation of

literary critics (or a certain sort) will champion the book along with

us.

(6).

The cover picture of the paperback edition, as many other examples of

the stamp

and line art within the text, can be seen as a disidentificatory

practice, as

defined by Muñoz. Here,

Lopez recuperates the image of the Latin bombshell, the tourist

attraction, and

the exoticized Latin music mystique, giving them all a twist. Framing the woman on top of a

motorcycle, in the context of what is called an all-girl road novel, places the erotic gesture of her partial

undressing in a different light.

One must now question whether she is prostituting herself and

her

identity for the dominant group (political, social, or gender) or

whether she

is flouting their rules, claiming her own sexual power, and laughing at

anyone

who doesn't approve. In the end,

the image captures much of its power from the mixture of its heavily

charged

sexist iconography with new elements suggestions of personal power,

humor, and

rebellion. For a discussion of the hard-back jacket cover, as well as

more

in-depth exploration of the physical elements of Lopez’s first three

works, see Laffrado.

(7).

Coincidentally, Puerto-Rican writer Letisha Marrero details a phone-sex

escapade with a “Canadian named John who happened to be incarcerated in

a

Florida jail cell,” one assumes a different John (143).

(8).

The schism between gay studies and queer studies is pronounced in some

of

Sedgwick's essays in Tendencies, where she explores an identity not

hemmed in

by restrictions of gender or sexual orientation. Thus,

a lesbian who loves, marries, and

sleeps with a gay man is not outside the realm of the queer. Similarly, a non-exclusionary outlook is

professed by Philip Brian Harper in several essays, where he reminds

the reader

that the involuntary visibility and invisibility of homosexuality is

much like

that of the homeless, people of color and other groups who exist

outside of the

confines of supposed normalcy.

(9).

An interesting comparison might be made with the literary production

and

critical reception of feminist writer Kathy Acker (1947-1997). Acker’s work, which incorporates a

brash treatment of sexuality and some truly innovative structural and

stylistic

elements, has received critical acclaim in postmodern circles, but also

exists

on the edge of the literary tradition to some extent.

One wonders how the element of race and

ethnicity of the authors, as well as the time period of their

production, may

contribute to their placement in the American canon.

(10).

The inescapability of desire as a textual element arises consistently

in queer

criticism. As suggested by

Muñoz, in reference to Marga Gómez's monologues delivered

from

the sexed space of her on-stage

bed, "The importance of such public and semi-public enactments of the

hybrid self cannot be undervalued in relation to the formation of

counterpublics that contest the hegemonic supremacy of the majoritarian

public

sphere" (1). Often

desire is entwined with the concept of abjection or repulsion, as in

Bergmann's

"Abjection and Ambiguity: Lesbian Desire in Bemberg's Yo,

la peor de todas" in Hispanisms

and Homosexualities and Ana García Chichester's "Codifying

Homosexuality as Grotesque: The Writings of Virgilio Piñera" in Bodies & Biases.

(11).

See Laffrado for a fascinating discussion of the representation of the

penis in

Lopez’s first three published works.

(12).

In the film Thelma and Louise, best friends flee from the authorities

in a

classic convertible after one of them accidentally kills a man who is

trying to

rape her. As they get further from

their origin geographically, the women realize that they also are

retreating

from the restrictions that society had placed upon them as women. They understand that they no longer can

live within such a system nor tolerate such prohibitions and

inhibitions, and

they plan and implement various acts of rebellion and revenge

throughout their

road trip. Nevertheless, the

“law of the father” comes ever closer to capturing them, and the

film ends as they act on the decision to drive full-speed toward a

cliff,

holding hands, the gleam of triumph strong in their eyes.

The implication, of course, is that

rather than force themselves to adhere to social expectations of

gender, they

willingly sacrifice their lives altogether, while holding out a tenuous

and

unarticulated hope that they will be catapulted into another dimension

where

their subjectivity will not be squelched.

Works Cited

Alvarez,

Julia. “Qué Dice la

Juventud?” Foreword. Border-Line

Personalities: A New Generation

of Latinas Dish on Sex, Sass, & Cultural Shifting.

Eds. Robyn Moreno and Michelle Herrera

Mulligan. New York: HarperCollins,

2004.

Bechdel,

Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

Bergmann,

Emilie L. and Paul Julian Smith, eds.

¿Entiendes?: Queer

Readings, Hispanic Writings.

Durham: Duke, 1995.

Chávez-Silverman,

Susana and Librada Hernández. Reading

and Writing the Ambiente. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 2000.

Cooper, Sara,

ed. The Ties That Bind:

Questioning Family Dynamics and Family Discourse in

Hispanic Literature. Lanham: U

P of America, 2004.

Eng, David.

“Out Here and Over There:

Queerness and Diaspora in Asian American Studies.” Social

Text 15.3-4 (1997): 31-52.

Juan

Flores. From Bomba to Hip-Hop: Puerto

Rican Culture and Latino Identity. Popular Cultures, Everyday Lives.

Eds.

Robin G. Kelley and Janice Radway. New York: Columbia UPress, 2000.

Foster, David

William and Roberto Reis, eds. Bodies

& Biases: Sexualities in Hispanic

Cultures and Literatures.

Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996.

Gaspar de Alba,

Alicia, ed. Velvet Barrios:

Popular Culture & Chicana/o Sexualities. New

York: Palgrave McMillan, 2003.

Geirola,

Gustavo. "Eroticosm and

Homoeroticism in Martín

Fierro." Bodies &

Biases. 316-332.

Goldman, Dara

E. “This Lan id Our Land: Erika Lopez’s Queer Latina

Sexcapades.” Paper presented at the Latin American Studies

Association’s International Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico, March

2006.

Gossy, Mary

S. "Aldonza as Butch:

Narrative and the Play of Gender in Don

Quixote." ¿Entiendes? 17-28.

Habell-Pallán,

Michelle. Loca Motion: The

Travels of Chicana and Latina Popular Culture.

New York: New York UP, 2005.

Hatfield,

Charles. Alternative Comics:

An Emerging Literature. Jackson: U P

of Mississippi, 2005.

Inness, Sherrie

A.

Tough Girls, Women Warriors and Wonder Women in Popular Culture: Feminist Cultural Studies, the Media and

Political Culture.

Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1999.

La

Fountain-Stokes, Lawrence.

“Cultures of the Puerto Rican Queer Diaspora.”

Passing

Lines: Sexuality and Immigration.

Eds. Bradley Epps, Keja Valens, and Bill Johnson González. Cambridge: David Rockerfeller Center for

Latin American Studies and Harvard University Press, 2005. 275-309.

Laffrado,

Laura. “Postings from Hoochie Mama: Erika Lopez, Graphic Art, and

Female

Subjectivity.” Interfaces: Women,

Autobiography, Image, Performance. Eds. Sidonie Smith and Julia

Watson. Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002. 406-429.

Lindstrom,

Naomi. E-mail communication. February 17, 2006.

Lopez,

Erika. Class visit to “Race,

Gender and Ethnicity”. DATE*.

Taught by Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano at

Stanford University.

---. Flaming

Iguanas (An Illustrated All-Girl

Road Novel Thing). New York:

Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Lugo-Ortiz,

Agnes T. "Community at Its

Limits: Orality, Law, Silence, and the Homosexual Body in Luis Rafael

Sánchez's '¡Jum!'"

¿Entiendes? 115-136.

---. "Nationalism,

Male Anxiety, and the

Lesbian Body in Puerto Rican Narrative." Hispanisms and

Homosexualities. 76-100.

Marrero,

Letisha. “Stumbling Toward

Ecstasy.” Border-Line Personalities.

131-151.

Molloy, Sylvia

and Robert McKee Irwin, eds. Hispanisms

and Homosexualities. Durham: Duke,

1998.

Muñoz,

José. Disidentifications:

Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics.

Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P,

1999.

Parr, James

A. "The Body in Context: Don

Quixote and Don Juan." Bodies

& Biases. 115-136.

Rebolledo, Tey

Diana. Panchita Villa and Other

Guerrilleras: Essays on Chicana/Latina Literature and Criticism.

Austin: U

of Texas P, 2005.

Rodríguez,

Ralph. “A Poverty of

Relations: On Not ‘Making Family From Scratch,’ but Scratching Familia.” Velvet Barrios. 75-88.

Schaefer-Rodríguez,

Claudia. "Monobodies,

Antibodies, and the Body Politic: Sara Levi Calderón's Dos mujeres." Bodies & Biases.

217-237.

Sedgwick, Eve

Kosofsky. Tendencies. Durham:

Duke, 1993.

Sifuentes

Jáuregui, B. "The Swishing of Gender: Homographetic Marks in Lazarillo de Tormes." Hispanisms and

Homosexualities. 123-140.

Solomon,

Melissa. “Flaming Iguanas, Dalai Pandas, and Other Lesbian Bardos.”

Regarding Sedgwick: Essays on Queer

Culture and Critical Theory. Eds. Stephen M. Barber and David L.

Clark. New

York: Routledge, 2002. 201-216.

Spiegelman, Art.

In the Shadow of No Towers. New York:

Pantheon, 2004.

Harper, Philip

Brian. “Gay Male Identities, Personal Privacy, and Relations of Public

Exchange: Notes on Directions for Queer Critique.” Social

Text 15.3-4 (1997) 5-29.

Yarbro-Bejarano,

Yvonne. “The Lesbian Body in

Latina Cultural Production.” ¿Entiendes?

181-197.

---. The Wounded

Heart: Writing on Cherríe

Moraga. Austin: U of Texas P,

2001.

Warner,

Michael, ed. Fear of a Queer

Planet.

Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1993.